Her Indian name, or at least one of her Indian names, the only one any of us know, is Tsupu. She is my great-great-grandfather’s mother, or my great-great-great-grandmother, and, again as far as any of us know, the last Native of Petaluma.

Not the city we know today, but the ancient Coast Miwok village of the same name. Certainly, she is the last to pass down any memory of the place. She is quite young, perhaps 14, when she leaves, beginning what becomes a chaotic, wholly incredible journey to find and keep a home in and about Sonoma County.

Though the village is abandoned once and for all after the 1838 smallpox epidemic claims its remaining citizens and though American farmers demolish its large midden, using the centuries-old refuge of decomposed shells for fertilizer, eradicating any trace of the village, Tsupu never forgets it. The last time she visits, she is completely blind, yet nodding with her chin to an empty hillside, she says “there,” as if she can see Petaluma plain as day, tule huts and fire smoke.

The village was a top a low hill, east of the Petaluma River, about three and a half miles northeast of the present city of Petaluma. Petaluma in Coast Miwok means “sloping ridge”, and, as is often the custom, gets its name from the distinct feature of the landscape associated with it.

Tsupu is the Coast Miwok word for “wild cucumber”. Perhaps it is a nickname. Natives are fond of giving nicknames. At some point, she is baptized Maria, and even later is referred to as Maria Chekka, or Cheka, suggesting Russian influence. There are also references to Maria Chica, suggesting Spanish or Mexican influence. She is born about 1820.

Mexican soldiers find her bare-breasted in a traditional tule skirt and tattooed under her chin indicating membership in one of two village moieties. She is taken to General (Mariano Guadalupe) Vallejo’s fort near Sonoma. No one knows what happens there, or how long – days, weeks – she stays, before escaping and walking 50 miles through rugged terrain to Fort Ross, seeking sanctuary among the Russians, reputed to be kinder to Natives than the early Mexicans.

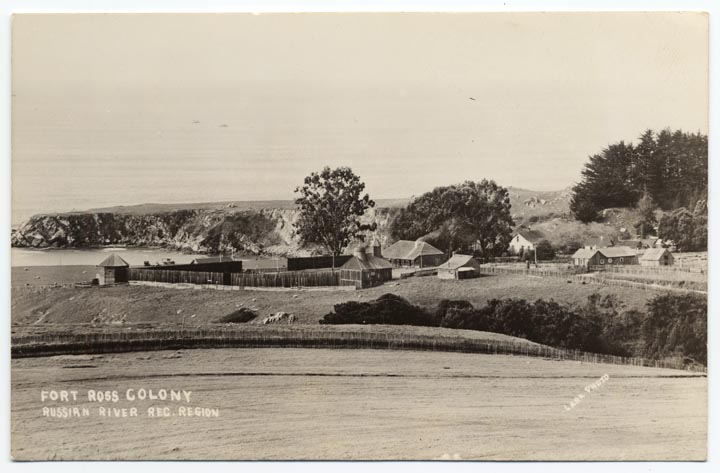

At Fort Ross, she marries Comtechal, listed in the Russian records as a “creole”, a man of Russian, Aleut, and Kashaya Pomo heritage. When the Russians abandon Fort Ross in 1842, after depleting the sea otter population, Natives become vulnerable to Mexican and early American Indian slave traders.

Leaving Comtechal safe in an isolated Kashaya Pomo village, Tsupu travels south to Bodega Bay where she becomes the maid and mistress of Captain Steven Smith, a sea captain from Boston who builds and operates the first steam-generated saw mill on the West Coast. She gives her children with Comtechal the name “Smith” to protect them from roving slave traders, She has two children from Captain Smith, and as Indians, they too are safe with the name Smith.

When Captain Smith, several years older than Tsupu, dies in 1855, his widow leaves Tsupu and her descendants a plot of ground overlooking Bodega Bay for a cemetery.

Soon thereafter, Tsupu rejoins Comtechal in a small Native settlement north of the bay. By this time, she has secured such a position of influence throughout the region that Americans, seeing her approach in horse and buggy, tip their hats in respect, often confusing her for Captain Smith’s actual widow. She speaks Coast Miwok, Kashaya Pomo and Southern Pomo, and Spanish, Russian, and English.

She dies two weeks after Comtechal. It is said that she is barefoot and sitting upright in a chair next to his pallet bed, wearing her finest clothes, a handmade late 19th Century black dress with a bustle and fitted bodice, and a silk mantilla from the Mexican California period that covers her face and reaches to the ground, as if she has dressed for her own funeral.

At the time of European contact estimates are that as many as 20,000 individuals from Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo Nations live in what is today Marin and Sonoma Counties. The Spanish march us into the missions, first Mission Dolores, then Mission San Rafael and Solano (Sonoma).

The early Mexicans enslave us, following policies of indentured servitude, vagrancy laws, and convict leasing – policies that are incorporated into the state of California’s first piece of legislation, the 1850 Act For the Government and Protection of Indians, legalizing Indian slavery, which is not repealed until 1868, three years after the end of the Civil War.

Today, all 1,458 enrolled citizens of The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, trace their ancestry back to one of 14 Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo survivors, most of them women, mainly wives or concubines of early Mexicans or Americans. Tsupu, ancestor to nearly a quarter of the Tribe, is one of them.

________

Greg Sarris is serving his fourteenth elected term as Chairman of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria and holds the position of Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria Endowed Chair of Sonoma State University.

He has published several books, including Grand Avenue (1994), an award-winning collection of short stories, which he adapted for an HBO miniseries and co-executive produced with Robert Redford. His most recent book, How a Mountain Was Made, was published in October 2017.