Between 1864 and 1869, thousands of Chinese migrants toil at a grueling pace and in perilous working conditions to help construct America’s first transcontinental railroad. The western portion begins in Sacramento and ends near Salt Lake City.

The line literally and figuratively reshapes the physical, economic, political, military, and social landscape of the American West and connects California to the rest of the nation.

Before the line is completed, travel between California and New York takes at least six to eight weeks. Afterward, it takes six to eight days. The railroad transforms the state, and Chinese immigrants make it happen.

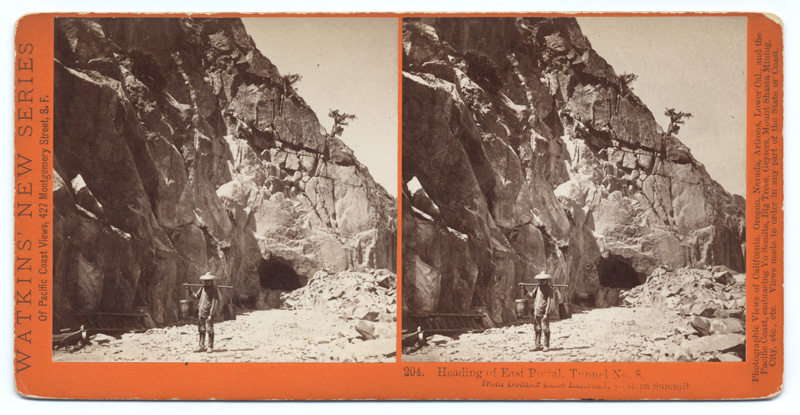

Their work ranges from basic unskilled tasks, such as moving earth and snow, to highly skilled tasks, such as blacksmithing, carpentry, tunneling, and drayage. The Chinese are cooks, medical practitioners, masons, loggers, and line managers. They clear the roadbed, lay track, handle explosives, bore tunnels, and construct retaining walls. Virtually all work is done by hand, with hand tools. No power tools or power-driven machinery is used in the construction work.

The most daunting construction challenge is to get the line through the Sierra Nevada, with its solid granite mountains and extreme climatic conditions that make work almost always treacherous. The Chinese carve 13 tunnels using only picks, black powder, and their muscle. It takes two years to get through Summit Tunnel, near Donner Lake. Work doesn’t stop through two terrible winters that see some of the heaviest snow fall on record.

Up to 20,000 Chinese men work for the Central Pacific Railroad, the company responsible for the western portion of the Transcontinental. Some have lived in California since the 1850s when they arrive from Southern China. Others come later in the 1860s to work specifically on the rail line. As many as 1,200 perish in horrific deaths, including accidental explosions, rock avalanches, and snow slides. Despite their efficiency, endurance, intelligence, and dependability, however, the Chinese work longer hours for less pay than their white peers. They also must pay for their own food. Historians estimate that they cost the company between one-half and two-thirds of white workers.

After the completion of the railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah in May 1869, some of the Chinese return to China, but many stay in the United States to work on other construction projects around the country.

Others travel on the newly constructed rail lines to help found Chinese communities in New York, Chicago, the Mississippi delta, and elsewhere.

They form the foundation of Chinese America in California and the nation.

Truckee, now a vacation hub, serves as a base of railroad operations, including housing many of the Chinese during and after the railroad construction. A Chinese community thrives there for years before vigilantes murder them, drive them out, and burn down their quarter. The implementers of the “Truckee Method” are all too successful. Today, there is little to indicate that Truckee has been home to one of the largest Chinese communities in America.

Chinese labor makes railroad barons Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins fabulously wealthy. They become memorialized as the “Big Four.” Universities, museums, and abundant historical markers bear their names and perpetuate their “hallowed” reputations. The workers reap no such profit and are often omitted in published histories. Many die poor, with no families to remember them, and no one to record their humble identities and mighty works.

________

Gordon H. Chang is the Oliver H. Palmer in Humanities, Professor of History, and the Senior Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education at Stanford. He is the author of “Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and co-editor of “The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad” (Stanford University Press). He is a fourth generation Californian.

Gordon H. Chang is the Oliver H. Palmer in Humanities, Professor of History, and the Senior Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education at Stanford. He is the author of “Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and co-editor of “The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad” (Stanford University Press). He is a fourth generation Californian.