As a boy growing up in Suffolk County on Long Island, I climb the tops of the highest hills with my mother and father and my two brothers, Daniel and Adam. Climbing hills in summer becomes a family ritual.

Before I’m 10, I learn to feel good about myself and the whole world when we trudge up Jayne’s Hill, the highest point on the island, or meandering up West Hills, where Walt Whitman was born.

When I move to Northern California, I encounter a new and different species of hills. The hills in Sonoma, where I settle, and in Marin, which I often explore, look bigger, higher, more inviting and yet more remote, too, than the hills I have known. Driving on Highway 101, I see the hills in the distance and know that I want to go there and scale them. I know, too, that at the peaks I would turn and look back at the valley floor and see the way I had come.

But then something strange happens. I find that as I approach those hills they become more inaccessible and more forbidding. No road seems to lead directly to any hill on the horizon. Even if a road does eventually take me to the foot of a hill, after meandering this way and that, I find fences, some of them barbed, and signs that warn me to keep out, keep off, and no trespassing allowed.

In the hills of Long Island, I would have ignored those signs and kept on walking. But here I feel like an outsider, and not knowing the customs of Northern California I keep my distance. I learn to appreciate the splendor of the hills from afar, and to know the seasons by gazing at the face of those hills as though looking at a big clock that tells the time of year.

In July, the hills beyond my backyard turn brown, and then golden brown, and then an even more brilliant golden brown. The colors make me think of lions in Africa, though I’ve never been there.

In August, the hills turn orange, purple, magenta, and other colors, too, for which I haven’t yet found the right words. Flowers come out and cascade down the hillsides. I wonder how that’s possible since it hasn’t rained since April, and obviously no one has bothered to irrigate these stretches of land sometimes dotted with cattle and sheep. As the days get hotter and the land grows more parched, the landscape seems to become even more beautiful, and I wish that time might stop here and linger.

In the dead heat of summer is when I know the face of the true California, the real California. That’s the California I have come to love as I once loved Long Island.

I don’t want to think about the rain that will fall steady for days and the sound of the swelling creeks. I don’t want to imagine the way the hills will turn pale green, and then bright green and then an emerald green. I want to hear forever that eerie sort of silence that seems to sweep across the hills, making me feel strange, alone and alive.

Over the years I have found ways to walk into the hills. I wander up and down the golden and purple hills, following dry creek beds, and I stand under a solitary oak and look back at the valley.

I don’t begin to feel like a native by surfing, hot tubbing, driving a car along the Pacific, sipping Chardonnay, or any of those other ways that Californians are supposed to define themselves, though I have also done all those things.

The hills of California tested me, found me fit and read me my rights. Sometimes I still long for the hills of Long Island,. but I’ve been away so long that I can’t remember how the hills smell in summer, or what the wind sounds like when it blows across the well-worn peaks.

Now, I can’t help but smell the hay, the sage, the lavender and the horses: the smell of my golden California.

_______

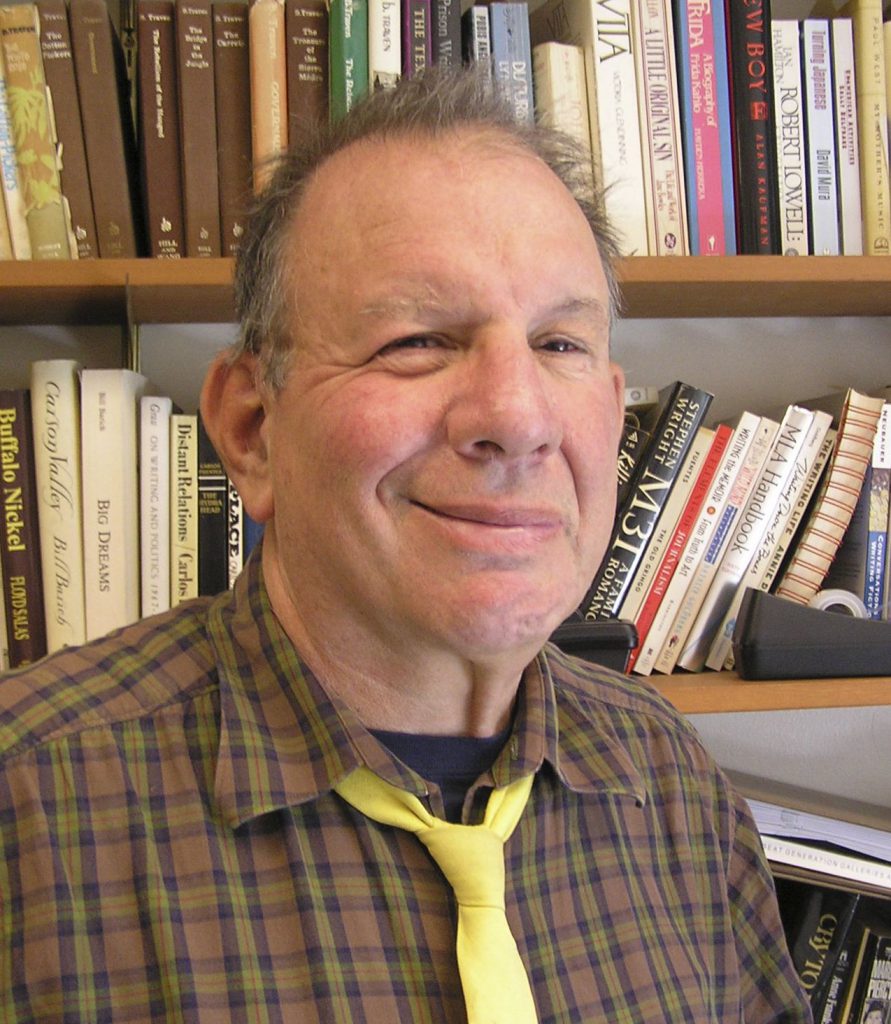

Jonah Raskin has lived in California since 1976.

For 30 years he taught literature, law and marketing and he has written about California history and culture In several books including American Scream and The Radical Jack London and in three noir novels set in Sonoma.