Emily Pitts Stevens occupies a hallowed position in the pantheon of early suffrage advocates in California.

As a 25-year-old teacher of night classes for working women in San Francisco, she buys the California Sunday Mercury, a journal of romance and literature which she eventually renames The Pioneer, the West’s first suffrage newspaper. A one-year subscription costs $3.

It is a newspaper for women, created by women. Pitts Stevens hires women to set type for her newspaper in defiance of the Printer’s Union and pushes for an eight-hour workday for all women. In her first issue as publisher, she refers to women as “revolutionists,” writing:

“The wrongs of woman, the many abuses she has suffered, have at last [been] aroused from their lethargic sleep.”

The feisty journalist, called “Pittsey” by her detractors, backs up her talk with action, creating a 19th-century version of a media frenzy on the evening of June 24, 1872 when she and four fellow suffragists decide to take in a lecture at the city’s venerable Platt’s Hall by who the newspapers call “Mrs. Frost,” a noted anti-suffragist.

The speaker says suffrage would be destructive to Family, Church and State. She accuses suffragists of supporting free love and rejecting the Bible. Sitting in the front row, Pitts Stevens and her colleagues laugh sarcastically and make loud derisive comments.

San Francisco Assemblyman David Meeker jumps to his feet. When he shouts at the hecklers, “I intend to make you behave yourselves, you’re behaving disgracefully,” he’s met with a mix of cheers and hisses.

“You will find it difficult to make us do anything we don’t like,” Pitts Stevens replies.

Mrs. Frost, the anti-suffragist speaker, then joins the fray.

“This is the class of women who would elbow their way to the polls,” Frost says said. “I suppose we have here a sample of what we might expect if women were in power.”

As the lecture ends and the crowd files out, Pitts Stevens accosts Meeker, a former business partner of Leland Stanford, challenging him to a duel.

“You insulted me in a public hall and I demand the satisfaction usual among gentlemen,” she tells him. Meeker scoffs Pitts Stevens stands her ground. “Will you apologize?” she demanded.

“Of course not,” Meeker replies, at which point Pitts Stevens reaches into her pocket, pulls out a derringer and aims it at the startled Assemblyman’s chest.

According to various news reports, a bystander quickly grabs hold of the pistol, and convinces Pitts Stevens to put the weapon back in her pocket.

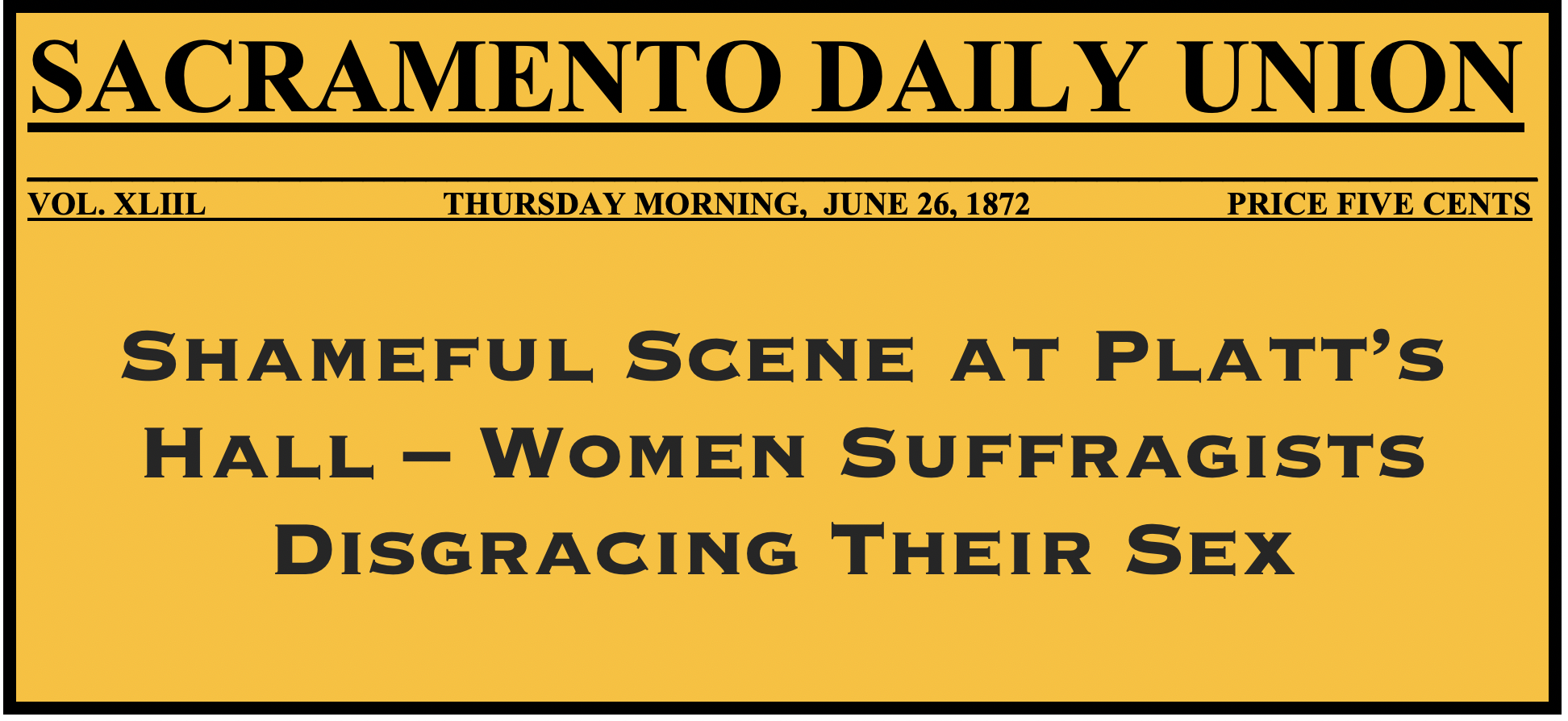

Newspapers – from coast to coast – seize on the incident The Sacramento Daily Union headline brands the episode “shameful.” The Mariposa Gazette characterizes her behavior as “naughty,” but it admires her fighting spirit. The San Francisco Call is more muted, saying the incident is “very unfortunate” and that “the ladies allowed their zeal for the cause to make them forget the rules of politeness and good order.” meeker, says the Call, “forgot that he was talking in public to a woman.”

For her part, Pitts Stevens later admits she had a gun, but denies aiming it at the assemblyman.

Emily Pitts Stevens continues to use her newspaper as a pulpit to unabashedly preach against gender inequality. Later she supports temperance and joins the prohibition party in 1882.

In a series of Capitol speeches, she packs the galleries and forcefully urges the all-male Legislature to give women the vote. In 1911, five years after her death, California’s male voters do what she asks.

______

Steve and Susie Swatt are coauthors of Paving the Way: Women’s Struggle for Political Equality in California.