Catherine Hittell is passionate about wildlife preservation. Saving the meadowlark from extinction, in particular. During the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century, the songbird is a popular meal.

“A meadowlark, cooked, gives one person pleasure for, at most, 10 minutes,” Hittell says in an 1885 San Francisco Examiner interview. “A living one gives pleasure to a whole community all its life long.”

In the early 20th Century, the options for women to participate in business and politics are limited, at best. To expand their influence, many women join clubs that push for civic improvements.

Black women’s clubs promote African-American achievement mostly through community boosterism, community service and cultural activities. White women’s clubs like Hittell’s California Club, founded by Laura Lyon White in 1897, often focus on conservation.

Described by the Los Angeles Times as a “gentle sweet-faced little woman,” Hittell is born into a prominent San Francisco family and is among the earliest female graduates at the University of California in 1882.

The Times neglects to say she is both energetic and persistent. Hittell and her California Club colleagues lead petition drives and public education campaigns to protect the meadowlark. They sponsor legislation to protect the birds. They lobby lawmakers. She also criticizes hunters.

At a gathering of governmental appointees assigned to recommend amendments to the state’s hunting laws, she pleads:

“You men are busy making laws to save the game for your hunting. Don’t you think you might make just one little law to save the song birds for the women? That is all we want.”

After an unsuccessful effort to protect the meadowlark, a dejected Hittell writes to naturalist John Muir and tells him of a conversation with a man who lives in a San Francisco boarding house.

Hittell says the man told her “they had lark pie for breakfast and as there were 100 boarders in that house, it meant 100 ‘slaughtered innocents.’ ”

A supportive Muir writes back:

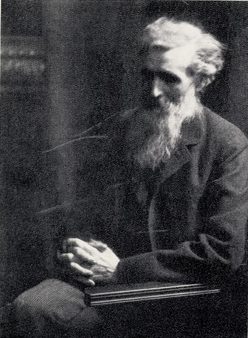

“Better far and more reasonable it would be to burn our pianos and violins for firewood than to cook our divine midgets of songlarks for food.”

In 1901, Hittell finally engineers success in the California Legislature with the state’s first bird-protection law, the Meadowlark Preservation Act, which makes it illegal to kill meadowlarks. According to the California Federation of Women’s Clubs, it’s the first piece of legislation in California written by a women’s club to become law.

For nearly two decades, Hittell and the law’s supporters, including the Audubon Society, successfully prevent repeal efforts by farmers and vintners who claim meadowlarks damage their crops.

At the same time, clubwomen and the Audubon Society score other victories, including introduction of nature study in schools, passage of legal protection for mourning doves and legislation prohibiting the trapping or slaughter of wild nongame birds.

Building on the successes in California, a national bird protection campaign culminates in a federal law outlawing the import of wild-bird feathers into the country.

Hittell also teams with her sister club members in a second major conservation cause, a crusade that saves ancient, majestic redwoods known as the Calaveras Big Trees from the logger’s axe. But she remains best known, as the Los Angeles Times characterizes her, as “the savior of the songsters.”