On March 29, 1942, three months after America enters World War II, Lieutenant General John DeWitt issues Public Proclamation No. 4, which begins the forced evacuation and detention of more than 100,000 West Coast residents of Japanese-American ancestry.

The “evacuees” receive as little as 48-hour notice to pack a suitcase and leave their homes and livelihoods.

“We saw two soldiers, marching up our driveway, carrying rifles with shiny bayonets on them. They stomped up the porch and with their fists began pounding on the door. The way I remember it, the whole house seemed to tremble. My father came out and answered the door and, literally at gunpoint, we were ordered out of our house,” actor George Takei, a five year-old boy in 1942, recounts on Late Night with Seth Meyersin 2019.

Dewitt’s action stems from Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, giving the Secretary of War the authority “to exclude any and all persons, citizens, and aliens from designated areas in order to provide for security against sabotage and espionage. …”

Over the next four months, approximately 112,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry are removed from their homes and sent first to “assembly centers,” often racetracks or fairgrounds. After being forcibly removed from their home, Takei and his family are shoehorned into a horse stall at Santa Anita.

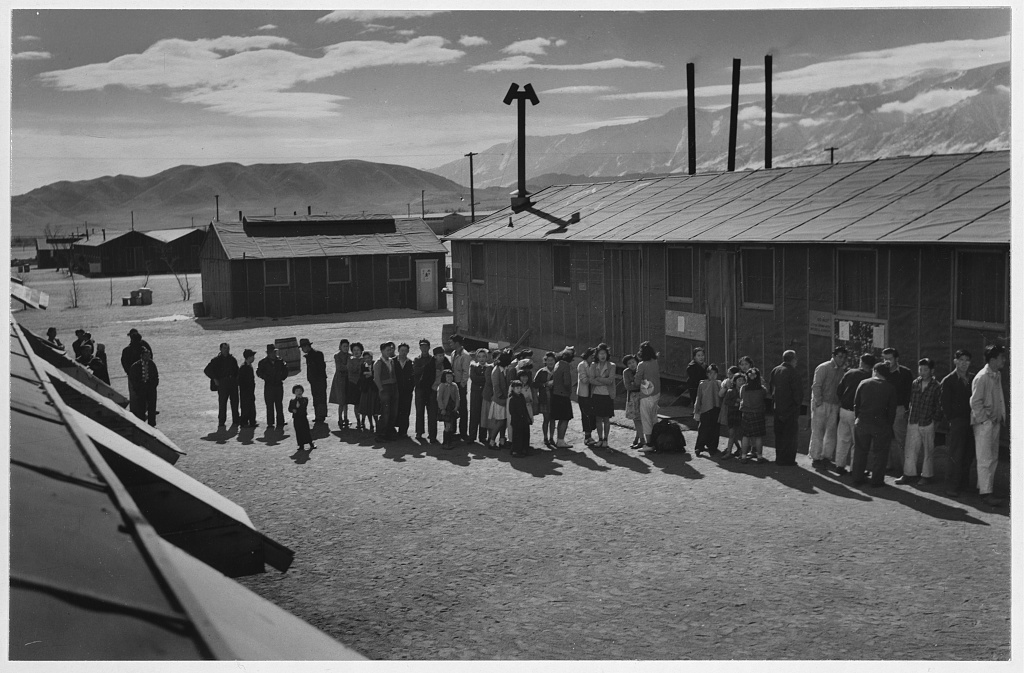

From the “assembly centers,” the Japanese Americans are assigned to “relocation camps” where they will remain until the war’s end.

Nearly 70,000 of those forced into the camps are American citizens. Prior to World War II, California is home to more Japanese Americans than any other state.

These “camps” are bleak and barb-wired, located mostly in desolate areas of Arizona, Arkansas, California, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. Families are crammed in drafty, shared barracks, with communal dining and latrines.

Told the incarceration is for their protection, one Japanese American asks why the guns of the guard towers are pointed inward rather than outward.

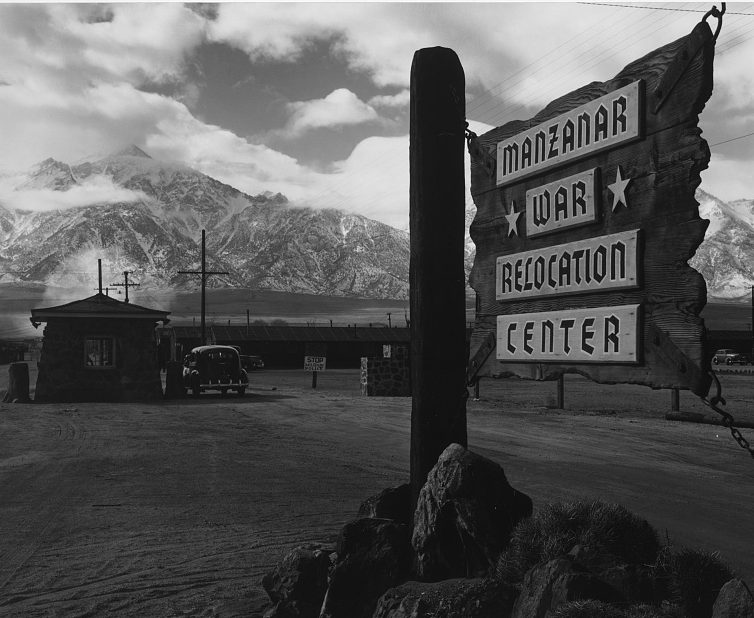

Manzanar, one of the California camps, near Independence on Highway 395, is a national monument. It houses 10,000 Japanese Americans before its closure in November 1945. Also a national monument is the Tule Lake Relocation Center in Modoc County, near the Oregon border. Tule Lake is where the “dissidents” in other camps are sent.

The War Department insists the forced relocation protects national security. The US Department of Justice raises logistical and constitutional objections to the action but in vain.

Three incarcerated Japanese Americans file lawsuits challenging the camps. In the landmark case brought by Fred Korematsu in 1944, a majority of the US Supreme Court upholds the camps. But three justices offer “fiery” dissents. Internment is “legalization of racism, writes Justice Frank Murphy in his dissent:

“Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting, but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States.

“All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land. Yet they are primarily and necessarily a part of the new and distinct civilization of the United States. They must, accordingly, be treated at all times as the heirs of the American experiment, and as entitled to all the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.”

“No reasonable relation to an ‘immediate, imminent, and impending’ public danger is evident to support this racial restriction, which is one of the most sweeping and complete deprivations of constitutional rights in the history of this nation in the absence of martial law.”

As the war ends and the camps close, Japanese Americans return to their former homes, often facing discrimination and prejudice.

Many are able to resume their lives but many have lost their jobs during relocation and others now discover their homes and property are gone too.

President Harry Truman signs Executive Order 9742 in June 1946 abolishing the War Relocation Authority that ran the camps.

Two years later, Truman signs the Japanese-American Claims Act, which allows the settlement of property loss claims by Japanese Americans forced into camps. Congress pays out $38 million to settle 23,000 claims for $131 million in damages. The final claim is paid in 1965.

At the same time the camps are in operation, the government assembles a combat unit of Japanese Americans for the European theater.

It becomes the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the most decorated unit of its size in United States military history. In two years, the 14,000 men who serve in the unit receive 4,000 Bronze Star Medals and nearly 9,500 Purple Hearts.

It isn’t until 1976 that President Gerald Ford repeals Roosevelt’s executive order — 30 years after the last camp closes.

In 1988, Congress passes Public Law 100-383, signed by President Ronald Reagan, that acknowledges the injustice of internment and provides $20,000 in reparations to persons placed in the camps that are still alive. Over 80,000 Japanese Americans receive the payment.

In February 2020, the California Assembly passes a resolution apologizing for the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and for earlier discriminatory policies like the prohibition on Asian immigrant purchases of agricultural lands in the Alien Land Law of 1913.

One of the reasons Manzanar is chosen as a historical site is the rich photographic record of life at the camp provided in part by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and Toyo Miyatake, a Los Angeles photographer who smuggles in a camera.

TOP PHOTO: Entrance to Manzanar, Ansel Adams/ Library of Congress