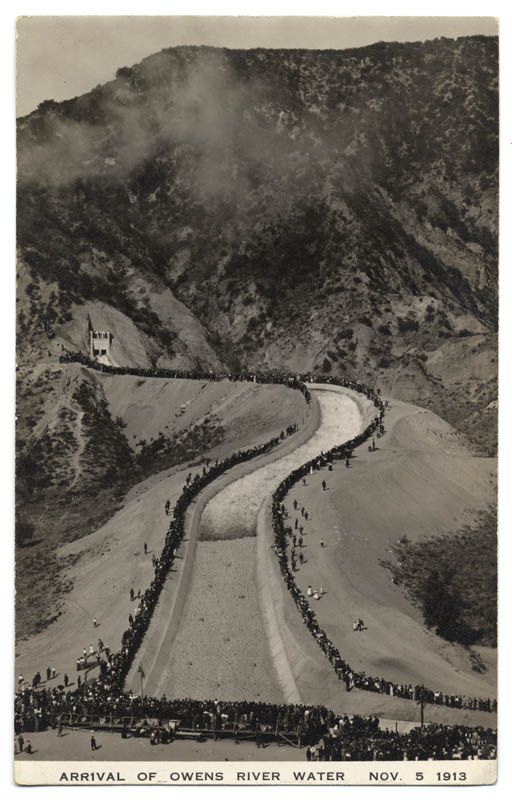

On November 5, 1913, an estimated 30,000 Angelinos watch water from the Owens Valley cascade into the San Fernando Valley through the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Work on the 223-mile canal starts five years earlier – over the strong but futile objections of the Eastern California residents of Owens Valley.

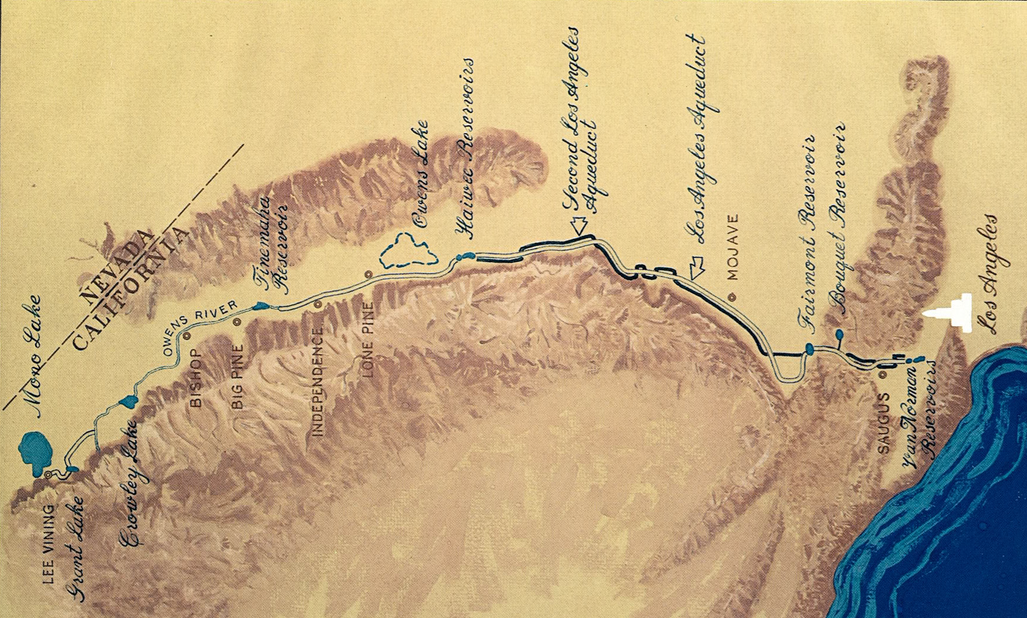

Owens Valley, altitude 4,000′, is fed by an alpine lake surrounded by towering mountains. The lake’s water is siphoned off with gravity doing much of the work in ferrying the lifeblood of suburban development hundreds of miles to Los Angeles.

At the same time, the area’s high altitude drains much of the humidity from the air before it reaches Owens Valley, drying the air and leaving the valley, without its lake, with no real source of water for ranching.

At the opening ceremony of the aqueduct, William Mulholland, Los Angeles’ city engineer — “The Chief’” — tells the crowd that the platform from which he speaks is “an altar, and on it we are here consecrating this water supply and dedicating this aqueduct to you and your children and your children’s children — for all time.”

Mulholland unfurls the flag on the rostrum, signaling the water gates be opened. The aqueduct lives up to it’s nickname – “Cascades” – and provides the needed ingredient for the massive growth of Los Angeles and the net worth of those who own San Fernando Valley real estate.

The additional water grows the City of Los Angeles explosively — its land area increased by more than 700 percent in the following two decades. Today, Los Angeles is the second most populous city in the United States.

After decades of legal wrangling, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and Inyo County agree in 1991 to jointly manage the valley’s water resources, setting flow regulations to reduce additional environmental damage to the valley.