So says Universalist and Unitarian minister Thomas Starr King on his San Francisco deathbed, March 4, 1864.

According to Charles Wendte’s 1921 biography of Starr King, the resonant orator — whose passionate sermons are instrumental in keeping California from joining the Confederacy during the Civil War — tells his wife, Julia:

“Do not weep for me. I know it is all right. I wish I could make you feel so; I wish I could describe my feelings. It is strange. I see all the privileges and greatness of the future. It already looks grand, beautiful. Tell them at home I went lovingly, trustfully, peacefully.”

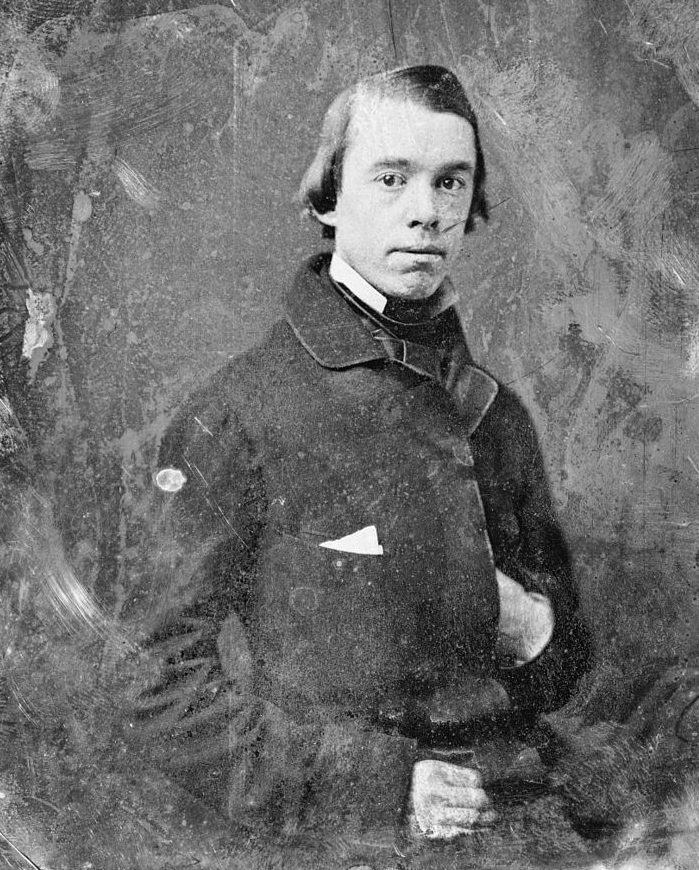

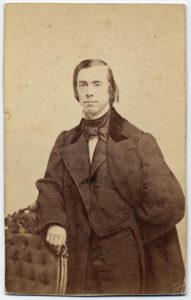

His slight build and boyish features make him appear half his 39 years.

Although not well known today, Starr King is considered so influential a century ago that in 1913 he is judged one of California’s two greatest heroes. Money is raised to cast a bronze statute of him that will stand in the National Statuary Hall Collection of the US Capitol. It takes awhile: Starr King’s statue is donated to the hall in 1931.

Although not well known today, Starr King is considered so influential a century ago that in 1913 he is judged one of California’s two greatest heroes. Money is raised to cast a bronze statute of him that will stand in the National Statuary Hall Collection of the US Capitol. It takes awhile: Starr King’s statue is donated to the hall in 1931.

Starr King is famous before he comes to California. His fame is built on his 11 years as minister of Boston’s Hollis Street Unitarian Church and as a popular lecturer who draws bigger and bigger crowds to hear him expound on Socrates, “Substance and Show,” “Existence and Life,” “The Laws of Disorder” and other topics.

An unwavering abolitionist, he’s also a naturalist and visits Yosemite shortly after arriving in California in 1860 and becomes an ardent supporter of the valley being protected from development.

After his death, Starr King’s Yosemite writings are collected in a book. An excerpt:

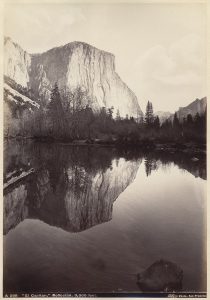

“The patches of luxuriant meadow with their dazzling green and the grouping of the superb firs, 200 feet high, that skirt them and that shoot above the stout and graceful oaks and sycamores, through which the horse path winds, are delightful rests of sweetness and beauty amid the threatening awfulness — like the threads and flashes of melody that relieve the towering masses of Beethoven’s harmony. The Ninth Symphony is the Yo-Semite of music…

“The immense escarpment (El Capitan) has no crack or mark of stratification. There is no vegetation growing anywhere on it, for there is no patch of soil on either front and no break where soil can lodge and a plant can grow. It is one block of naked granite, pushed up from below to give us a sample of the cellar-pavement of our California counties and to show us what it is that our earthquakes joggle. But on one face the wall is weather stained or lichen-stained with rich cream-colored patches; on the other face it is ashy grey. A more majestic object than this rock I expect never to see on this planet. Great is granite, and the Yo-Semite is its prophet!”

Starr King’s descriptions of the valley’s majesty contribute to the 1863 passage of legislation by California Senator John Conness, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, that preserves Yosemite — the first time the federal government sets land aside for such protection. In its March 5, 1864, obituary of Starr King, the Alta California writes:

“Such was his fame and influence that these letters had a wide audience in the East with a substantial effect upon Yosemite’s destiny.”

Starr King is also one of the first 100 white men to visit Lake Tahoe, then named Lake Bigler after former Democratic Gov. John Bigler. An 1863 sermon is titled “Living Water from Lake Tahoe.” One of his most famous naturalism sermons, “Lessons from the Sierra Nevada, contains some of his best-known naturalist writings. An excerpt from Starr King’s Tahoe sermon:

“I must speak of another lesson, connected with religion, that was suggested to me on the borders of Lake Tahoe. It is bordered by groves of noble pines. Two of the days which I was permitted to enjoy there were Sundays. On one of them I passed several hours of the afternoon in listening, alone, to the murmur of the pines, while the waves were gently beating the shore with their restlessness. If the beauty and purity of the lake were in harmony with the deepest religion of the Bible, certainly the voice of the pines was also in chord with it. What grandeur, what tenderness, what pathos, what heart-searchingness in the swells and cadences of its ‘Andante Maestoso,’ when the wind wrestles with it and brings out all its soul.”

California’s “Patriot-Preacher”

When Starr King arrives in California in April 1860, secession fever is high. Of the state’s 53 newspapers, seven support Lincoln. California’s U.S. Sen. William Gwin is an unscrupulous Tennessee native. California Chief Justice David Terry is a hot-tempered Texan. Gov. John Weller is a Lecompton – Pro-Southern—Democrat. So is his successor, Milton Latham, appointed to fill the Senate seat left vacant by the death of San Francisco’s David Broderick, killed by Terry in a duel.

In California’s political leadership, all are Democrats, a majority has strong Southern leanings and the lone voice railing against slavery – Broderick – is silenced.

Southern California leans pro-Confederacy and is squarely anti-Northern California. Weller signs legislation allowing the southern part of the state to break off and become the Territory of Colorado, which the idea’s supporters say will allow slavery. Writes William Day Simonds in his 1907 Starr King in California:

“California’s destiny in this critical hour was chiefly determined by the word and work of her patriot-preacher, Starr King.”

Starr King considers slavery an abomination. The Union — a united America – is sacrosanct. There is no separation of church and state in his sermons or his oratory:

“The Rebellion–it is the cause of Wrong against Right. It is not only an unjustifiable revolution but a geographical wrong, a moral wrong, a religious wrong, a war against the Constitution, against the New Testament, against God.”

Besieged with speaking invitations, Starr King accepts them all, whether major cities or mining camps. He barnstorms California, speaking from a podium draped with an American flag, defending the Union and supporting Abraham Lincoln. Starr King calls for an “emancipation proclamation” nearly two years before Lincoln issues one:

“O that the President would soon speak that electric sentence —inspiration to the loyal North, doom to the traitorous aristocracy whose cup of guilt is full! Let him say that it is a war of mass against class, of America against feudalism, of the schoolmaster against the slave-master, of workmen against the barons, of the ballot box against the barracoon. This is what the struggle means. Proclaim it so, and what a light breaks through our leaden sky! The war-wave rolls then with the impetus and weight of an idea.”

Lincoln ekes out a win in California with 32.3 percent of the vote – just 724 votes more than the 37,999 cast for the closest of his three opponents, Illinois Sen. Stephen Douglas. But the secessionist spirit doesn’t abate. On July 4, 1861, a Confederate flag waves over Los Angeles. Gen. E.V. Sumner, named commander of US troops on the Pacific Coast in March 1861, tells Lincoln’s War Department:

“The disaffection in the southern part of the state is increasing and is becoming dangerous and it is indispensably necessary to throw reinforcements into that section immediately.”

Starr King continues his speeches and sermons, in praise of patriotism and the Union and his parishioner, Leland Stanford, who is elected California’s first Republican governor September 4, 1861.

Satisfied that a Republican governor will hold any secessionist efforts in check, Starr King turns his energies to improving the appalling care of wounded soldiers, who often lack sheets and blankets. Medical staff is small and usually poorly trained. Hospitals are unsanitary and inadequate. In 1861, Rev. H.W. Bellows of New York creates the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a forerunner of the American Red Cross.

Starr King is the Sanitary Commission in California. To aid Union soldiers, the commission raises $4.8 million nationwide. Of that, Starr King convinces California to give $1.25 million, $200,000 from San Francisco. Simonds notes that California’s generosity comes despite an 1862 flood in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys that destroys $50 million in property and a drought the following year that wipes out the state wheat crop. On the day of Starr King’s death, the San Francisco Bulletin writes:

“The announcement of the death of Rev. Thomas Starr King startles the community, and shocks it like the loss of a great battle or tidings of a sudden and undreamed of public calamity. Certainly no other man on the Pacific Coast would be missed so much. San Francisco has lost one of her chief attractions; the State, its noblest orator; the country one of her ablest defenders.”

Flags throughout San Francisco fall to half-mast. Lawmakers in Sacramento pass a resolution declaring Starr King a “tower of strength to the cause of his country” and declare three days of mourning.

Draped in an American flag, King lies in state in the newly constructed San Francisco Unitarian Church at 133 Geary Street, surrounded by a military honor guard. An estimated 20,000 people pay their respects. San Francisco waives its ban on burials to allow Starr King’s sarcophagus to be placed on the church’s front lawn. It’s now located at the Unitarian church at 1187 Franklin Street built in 1889. Author Bret Harte writes “Relieving Guard,” a eulogy for his friend.

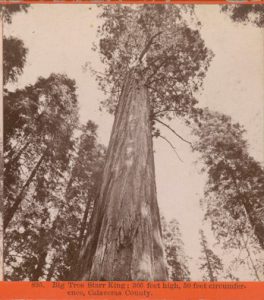

One of the giant sequoias in Calaveras Big Trees is named “Starr King,” as is a 9,096-foot granite dome in Yosemite.

Seventy-five years after his statue is placed in the US Capitol, California’s state Legislature approves — with only one dissenting vote — Senate Joint Resolution 3 to bounce Starr King’s statue from the National Statuary Hall and replace it with one of Ronald Reagan.

The resolution is authored by Sen. Dennis Hollingsworth, a Murrieta Republican, who admits to the San Francisco Chronicle that he doesn’t know who Starr King is, adding, “I think there’s probably a lot of Californians like me.”

Hollingsworth tells the Chronicle that Starr King also wasn’t born in California although that criteria isn’t applied to Reagan, born in Illinois, or the other statue California has in the national hall — Father Junipero Serra, born in Majorca, Spain. The only “no” vote on the resolution comes from then Sen. Debra Bowen, later California’s Secretary of State from 2006 to 2014, who apparently is aware of Starr King’s contributions to the state.

In November 2009, Starr King’s statue is brought home and placed in Civil War Memorial Grove in Sacramento’s Capitol Park.

TOP IMAGE: Thomas Starr King. From the Wikimedia Commons.