Triggering a national and international outcry, the San Francisco school board issues an order on October 11, 1906, requiring all Japanese and Korean children to attend a separate “Oriental School” where Chinese pupils are already segregated. Japanese parents are enraged.

The Japanese government says the school board’s edict violates a 1894 treaty providing Japanese residents in the United States with the same rights as American citizens.

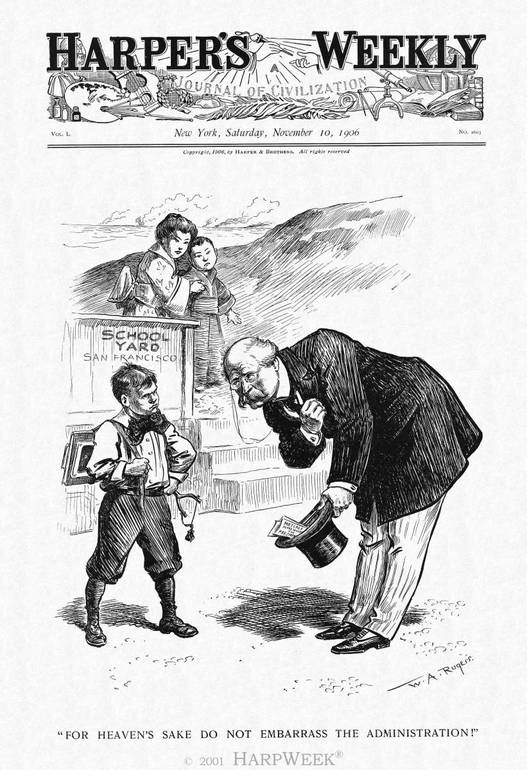

The action also puts at risk President Theodore Roosevelt’s foreign policy objectives with Japan, prompting the GOP chief executive to describe the school board’s action as a “wicked absurdity” in his annual message to Congress.

The action also puts at risk President Theodore Roosevelt’s foreign policy objectives with Japan, prompting the GOP chief executive to describe the school board’s action as a “wicked absurdity” in his annual message to Congress.

A city “should not be allowed to commit a crime against a friendly nation,” Roosevelt insists.

“Throughout Japan, Americans are well treated and any failure on the part of Americans at home to treat the Japanese with a like courtesy and consideration is by just so much a confession of inferiority in our civilization.”

Japanese laborers don’t come to California until after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 halts Chinese immigration. Unlike some other parts of the state, in San Francisco many Japanese immigrants become store and restaurant owners. They live throughout the city, unlike Chinese residents who are centered in Chinatown.

In 1906, there are 93 Japanese students attending 23 schools across the city. Twenty-five of the students are native-born United States citizens. And while the school district has a policy dating back to 1893 of segregating Japanese students — as they do Chinese pupils — there aren’t enough Japanese students to justify the expense of building them their own school.

Chinese students are barred from even attending school in San Francisco from 1880 to 1895. A court ruling holding that Chinese students have a right to attend public schools goads the district into opening a school for Chinese students in 1895.

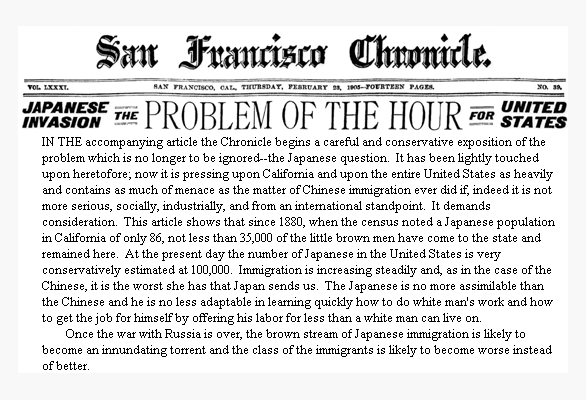

As the Japanese population of California grows in the early 1900s, labor unions begin to fling the same falsities about the Japanese that they leveled against the Chinese.

Besides baselessly blaming Japanese immigrants for a variety of social ills, the unions claim the Japanese will rob white workers of jobs by accepting lower wages.

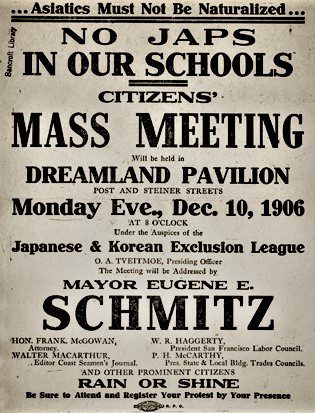

The 1901 campaign platform of San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz includes educating “all Asiatics, both Chinese and Japanese” in separate schools.

In 1905, the San Francisco Chronicle fuels anti-Japanese sentiment with a series of articles on Japanese immigration.

Unions form a front group — the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League, later the Asiatic Exclusion League — and start chapters throughout California and in other states. The league’s goal is halting all immigration from Asia to ensure “the perpetuation of the Caucasian race upon American soil.”

The exclusion league petitions the school district to enforce its 1893 segregation policy for Japanese students — and also apply it to the three Korean students also enrolled in San Francisco schools.

The school district says the school for Chinese students is full and the budget doesn’t allow for construction of a new school for 96 pupils.

Then Mother Nature intervenes. Most of the city is destroyed by the April 18, 1906 earthquake and subsequent fires. When the Chinese Primary School is rebuilt, it is only at half capacity because of the number of Chinese families who depart the city after the earthquake.

Those empty seats can be filled with Japanese and Korean students, the district decides. They rename the institution the Oriental Public School.

Japanese parents file suit. Chinatown, where the Oriental School is located, is a long way from many of their homes. Segregation violates the Treaty of 1894, the families contend. They also complain to both the local Japanese consul and the Japanese ambassador in Washington D.C.

Newspapers in Japan seize on the issue, echoing the parents’ anger and inflaming Japanese public opinion against the school district and the United States.

Roosevelt quickly acts to end the district’s policy and mend fences with Japan.

Hoping to cow the district into submission, Roosevelt directs the U.S. Department of Justice to file a lawsuit against the school district. The district, Mayor Schmitz and Gov. George Pardee, a Roosevelt supporter, insist they won’t back down without limits on Japanese immigration.

“It is safe to say that the President, when he penned that portion of his annual message upon the opening of Congress in which he refers to the treatment of the Japanese in the San Francisco schools, was not aware of the conditions on this coast, especially in California,” Pardee says in his second biennial message to the Legislature.

“Neither the Japanese nor the Chinese appear to be capable of absorption and assimilation into the mass of our people. Neither race has, apparently, any desire to renounce allegiance to its mother country and become, in the true sense of the word, citizens of the United States.”

Pardee signs a joint legislative resolution urging the federal government to protect the “Pacific Coast from the heavy influx of Japanese.”

Roosevelt satisfies both Japan and San Francisco through a “gentleman’s agreement,” in which the district rescinds its segregation policy for Japanese students and, in return, Japan promises to tacitly deny visas to laborers seeking to immigrate to the United States.

Roosevelt’s “gentleman”s agreement” of excluding Japanese laborers from coming to the United States is replaced by the 1924 Immigration Act which bars all Asians from entering the country. It remains on the books until 1965.