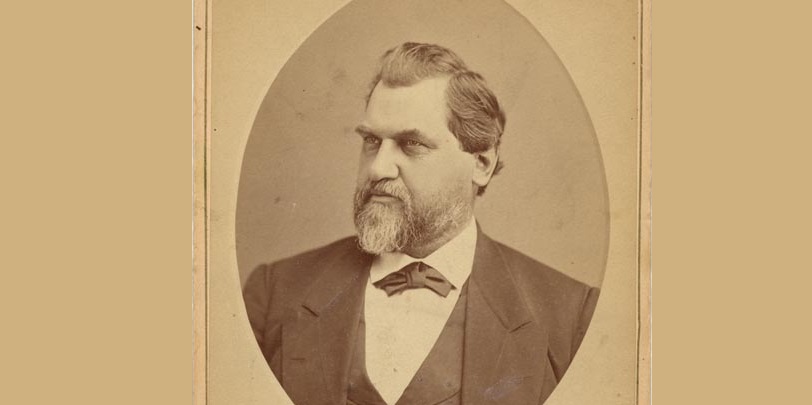

On a chilly, wet January 8, 1863, invited dignitaries and passers-by gather at K and Front Streets in what’s now Old Sacramento to watch the ceremonial beginnings of the first transcontinental railroad. Only a few weeks before, intense winter rains and swollen rivers flooded Sacramento. This morning it also rains but clears by noon. With straw spread atop the mud, Gov. Leland Stanford – who is also the president of the Central Pacific Railroad — pushes a silver shovel into pre-dried soil, “breaking ground” for his company’s new enterprise. Stanford tells the crowd:

“The day is not far distant when the Pacific will be bound to the Atlantic by iron bands that shall consolidate and strengthen the ties of nationality and advance with giant strides the prosperity of our country.”

Breaking ground is one thing, actual construction another. All rails and locomotives — nearly everything except timber — must make a five-to-eight month 18,000-mile journey from East Coast ports around Cape Horn to California. The Civil War also makes steel and other supplies scarce. Besides materials, labor is in short supply. Men who travel to California come to make their fortune, not lay track.

As a result, the Central Pacific’s first rails aren’t spiked until October 26. It takes four more years of blasting and tunneling – and the hiring of thousands of Chinese laborers — to climb up and through the Sierra Nevada. By spring of 1869 the line extends 690 miles to Promontory Summit, Utah where on May 10 the final golden spike is hammered joining the Central Pacific with the Union Pacific Railroad, which has been building west from Omaha.