While making his morning inspection of the sawmill he is building with John Sutter near the Maidu Indian village of Cullumah — now Coloma — on the American River, James Wilson Marshall notices a gleam at the bottom of the ditch through which the mill’s water runs.

He describes the moment in his Memoirs:

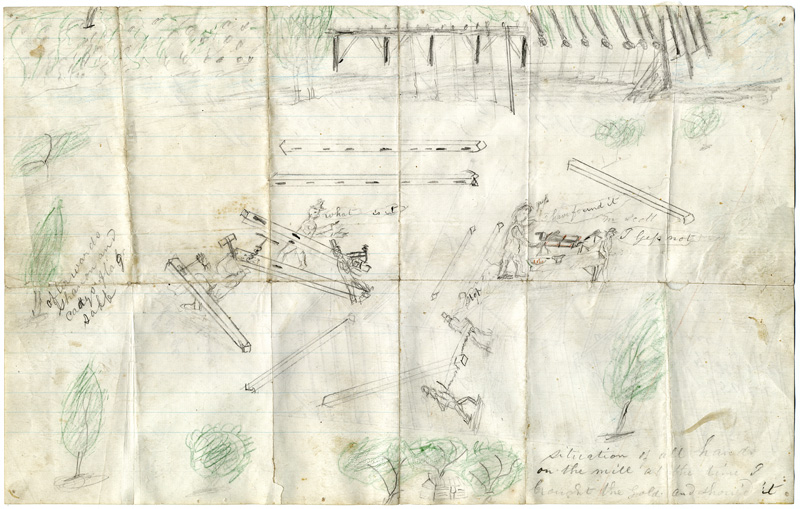

“I went down as usual, and after shutting off the water from the race I stepped into it, near the lower end, and there, upon the rock, about six inches beneath the surface of the water, I discovered the gold. I was entirely alone at the time. I picked up one or two pieces and examined them attentively; and having some general knowledge of minerals, I could not call to mind more than two which in any way resembled this –sulphuret of iron, very bright and brittle; and gold, bright, yet malleable; I then tried it between two rocks, and found that it could be beaten into a different shape, but not broken.

I then collected four or five pieces and went up to Mr. Scott (who was working at the carpenters’ bench making the mill wheel) with the pieces in my hand and said:

“ ‘I have found it.’

” ‘ What is it?’

” ‘Gold.’

” ‘That can’t be.’

” ‘I know it to be nothing else.’ “

Marshall journeys 45 miles southwest to Sacramento to share the discovery with Sutter. Sutter remembers it this way:

“It was a rainy afternoon when Mr. Marshall arrived at my office in the Fort, very wet. I was somewhat surprised to see him, as he was down a few days previous; and then, I sent up to Coloma a number of teams with provisions, mill irons, etc., etc. He told me then that he had some important and interesting news, which he wished to communicate secretly to me, and wished me to go with him to a place where we should not be disturbed, and where no listeners could come and hear what we had to say. I went with him to my private rooms; he requested me to lock the door; I complied, but I told him at the same time that nobody was in the house except the clerk, who was in his office in a different part of the house…. I forgot to lock the doors, and it happened that the door was opened by the clerk just at the moment when Marshall took a rag from his pocket, showing me the yellow metal. He had about two ounces of it but how quick Mr. M. put the yellow metal in his pocket again can hardly be described…

“As soon as (the clerk) had left I was told, ‘Now lock the doors; didn’t I tell you that we might have listeners?’… Then Mr. M. began to show me this metal, which consisted of small pieces and specimens, some of them worth a few dollars; he told me that he had expressed his opinion to the laborers at the mill, that this might be gold; but some of them were laughing at him and called him a crazy man, and could not believe such a thing.

“After having proved the metal with aqua fortis, which I found in my apothecary shop, likewise with other experiments, and read the long article “gold” in the Encyclopedia Americana, I declared this to be gold of the finest quality, of at least 23 carats. After this Mr. M. had no more rest nor patience, and wanted me to start with him immediately for Coloma….”

At Coloma, the following day:

“We went to the tail-race of the (saw)mill, through which the water was running during the night …. After the water was out of the race we went in to search for gold. Small pieces of gold could be seen remaining on the bottom of the clean washed bedrock. I went in the race and picked up several pieces of this gold, several of the laborers gave me some, which they had picked up, and from Marshall I received a part. I told them that I would get a ring made of this gold as soon as it could be done in California; and I have had a heavy ring made, with my family’s coat of arms engraved on the outside, and on the inside of the ring is engraved, ‘The first gold, discovered in January, 1848.’ ”

Marshall and Sutter decide the less known about the discovery, the better. Surprisingly, that works for a few months until word of gold on the American River reaches San Francisco in May 1848. Contemporary accounts say the city empties and the populace races north. Within weeks, the news spreads throughout the state.

Partly to boost his political agenda, President James Polk fans the frenzy by confirming Marshall’s find in his fourth annual address to Congress on December 5, 1848.

The Gold Rush that ensues brings immigrants from every continent and forms the core of the state’s unequaled diversity – although in 1849 more than 80 percent of the population is male. The flood of newcomers – California’s non-native population jumps from under 8,000 in 1848 to nearly 100,000 in 1849 – hastens admission as a state and propels America’s westward expansion. The state’s wealth allows it to dominate development of the rest of the West and the go-for-broke risk-taking of the goldfields kindles the state’s entrepreneurial drive.

Native Californians suffer from the massive influx of Anglo settlers. With their population already in decline from Spanish and Mexican intrusion, the state’s native population plummets from about 150,000 in 1848 to 30,000 just 12 years later.

Marshall, who claims he has supernatural gold-finding powers, leaves Coloma in 1853 after the area is overrun with prospectors. He drinks harder and grows increasingly bitter that he has profited so little from his discovery, which leads to $10 million in gold pulled from the ground in 1849 alone.

In 1872, the Legislature recognizes Marshall’s contributions to the state and awards him a $200 per-month pension. He moves to Kelsey, a few miles east of Coloma and opens a blacksmith shop. The pension ends in 1876 and when Marshall dies in 1885, age 75, there’s barely enough money to cover the cost of his funeral.

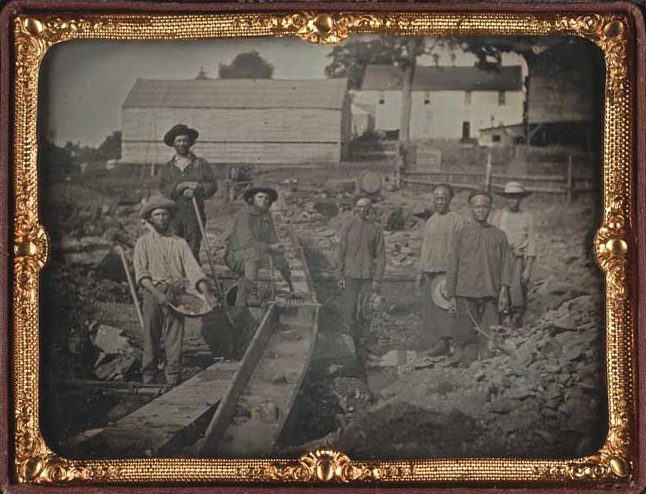

Featured Image: “Gold Mining in California” [1999-0359] California State Library

![Text of Capt. Sutter's account (left); Marshall's portrait in profile (right) above a view of Coloma with Sutter's Mill. Caption at right of Marshall's portrait: Portait [sic] of Mr. Marshal [sic], taken from nature at the time when he made the discovery of gold in California. Caption to the right of Sutter's Mill: View of Sutter's Mill or place where the first gold has been discovered.](https://cal170.library.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2002-0026.jpg)