On January 21, 1867, San Francisco Police Officer Armand Barbier rashly arrests Joshua Norton, self-proclaimed “Emperor of these United States” and “Protector of Mexico,” on charges of vagrancy. After it’s discovered Emperor Norton has money in his pockets, the charge is changed to lunacy, which still can mean a commitment to the state’s insane asylum in Stockton.

Formerly a successful San Francisco businessman, Norton loses his fortune – and likely his mind — trying to corner the market on rice in the early 1850s. In 1859, Norton begins supplying proof he is probably guilty as charged when he issues a proclamation – published by the San Francisco Bulletin on September 17 – declaring himself emperor and calling for a meeting in San Francisco on February 1, 1860 of representatives from the rest of the states “to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring, and thereby cause confidence to exist, both at home and abroad, in our stability and integrity.”

More proclamations follow. Many are phony, written by newspapers for laughs – or to grind a political agenda, says the San Francisco Virtual Museum. Among Norton’s actual pronouncements are dissolutions of Congress, the California Supreme Court and the United States. On August 12, 1869, Norton abolishes political parties. As printed in the Bulletin, Norton writes:

“Being desirous of allaying the dissensions of party strife now existing within our realm (I) do hereby dissolve and abolish the Democratic and Republican parties and also do hereby decree disfranchisement and imprisonment for not more than 10 nor less than five years, to all persons leading to any violation of this imperial decree.”

After a visit to observe the new state Capitol in Sacramento, Norton chides the city on its muddy streets and lack of a first class hotel. In a March 1872 proclamation in the Pacific Appeal, Norton calls for a bridge linking Oakland and San Francisco. Six months later, he orders the arrest of the leaders of both cities if they continue to thwart his will.

Emperor Norton dines gratis at city restaurants. Theater seats are reserved for him. He issues his own currency and levies taxes, usually 50 cents, which covers his daily rent at a rooming house at 624 Commercial Street. The address appears as his residence in the U.S. Census. His occupation: “Emperor.”

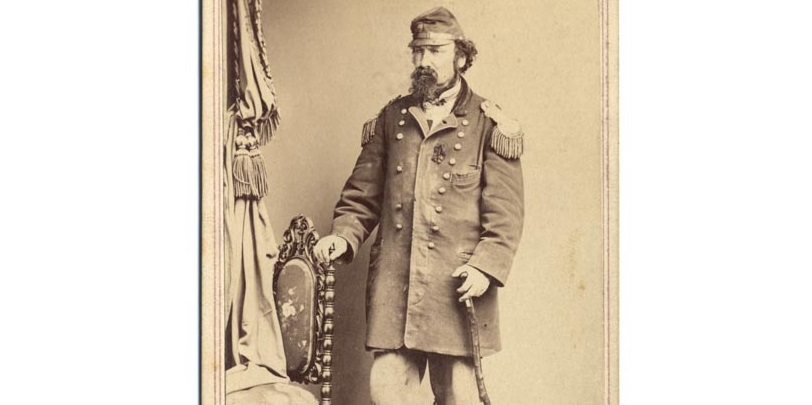

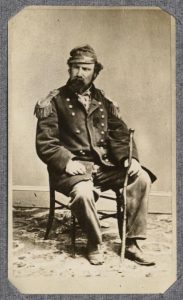

When surveying his realm, Norton wears a blue military uniform with gold epaulettes. He alternates it with a nut-brown Confederate uniform during the Civil War so as not to show favoritism. Two dogs, Bummer and Lazarus, are famous contemporaries of Norton that, according to some accounts, periodically accompany the emperor on his rounds. When Bummer dies in 1865, Mark Twain writes an obituary.

Not surprisingly, Norton’s arrest for lunacy prompts outraged editorials. From the Alta:

“Emperor Norton has never shed blood. He has robbed no one, and despoiled no country. And that, gentlemen, is a hell of a lot more than can be said for anyone else in the king line.”

The Evening Bulletin writes:

“(Emperor Norton) is being held on the ludicrous charge of ‘lunacy.’ This kindly Monarch of Montgomery Street is less a lunatic than those who have engineered these trumped up charges. As they will learn, His Majesty’s loyal subjects are fully apprised of this outrage. Perhaps a return to the methods of the Vigilance Committees is in order.”

Police Chief Patrick Crowley apologizes to Norton and releases him. Henceforth, Norton is smartly saluted by all police officers when he passes them on the street. The emperor’s reign ends January 8, 1880 when he falls over dead on California St. at Grant Avenue on the way to a lecture at the Academy of Natural Sciences. He’s believed to be 61. The funeral cortege stretches two miles. Writes Robert Louis Stevenson:

“In what other city would a harmless madman who supposed himself emperor … been so fostered and encouraged?”

TOP PHOTO: Norton I. by Bradley & Rulofson. California State Library image 2008-1614.