The three-person federal Public Land Commission is charged with determining the validity of Spanish and Mexican land grants in California. The 1851 legislation creating the commission is carried by one of California’s first U.S. senators, William Gwin. The law forces holders of Spanish or Mexican land grants to prove ownership, a process whose difficulty makes more land available for “Americans.”

This requirement to prove ownership is contrary to Article Eight of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican American Wars. In Article Eight, the United States pledge to respect Mexican and Spanish land grants.

But the land commission doesn’t, writes Hubert Howe Bancroft in Volume VI of his 1888 History of California:

“It was to the Californians owning lands under genuine and valid titles, seven eighths of all the claimants before the commission, that the great wrong was done. They were virtually robbed by the government that was bound to protect them. As a rule, they lost nearly all their possessions in the struggle before the successive tribunals to escape from real and imaginary dangers of total loss.

“The United States promised full protection of all property rights (but) practically by the system adopted they declared that every title should be deemed invalid until the holder had defended it at his own expense through from two to six fiery ordeals against a powerful opponent who had no costs to pay and no real interest at stake.”

Before dissolving on March 3, 1856, the Public Land Commission upholds 604 of the 809 claims filed by Spanish or Mexican land grant holders. All but three of the commission’s decisions are appealed to federal courts, however.

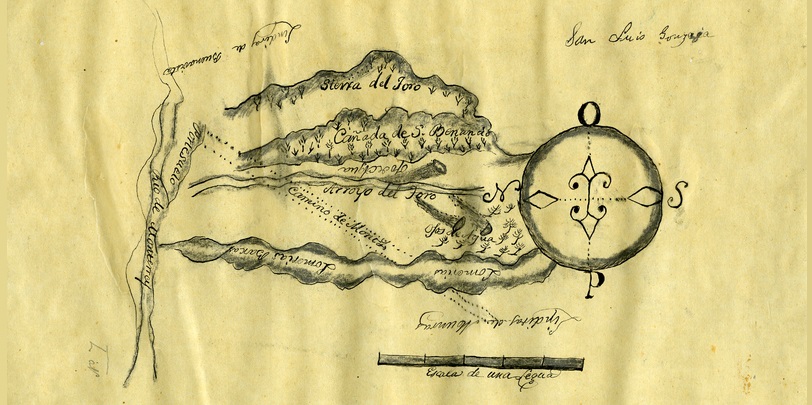

The expense of proving ownership causes many Californios to lose their holdings. Part of the problem is Gwin’s law requires “each and every person claiming lands in California by virtue of any right or title derived from the Spanish or Mexican government, (to) present the same to the said commissioners when sitting as a board, together with such documentary evidence and testimony of witnesses as the said claimant relies upon in support of such claims.”

Travel to San Francisco, where the commission is headquartered and holds all but one of its meetings, is costly, particularly when paying for witnesses. Lawyers are pricey. So is researching Mexican law and antiquated land grants. Writes W.W. Robinson in his 1948 book, Land in California:

“Up and down California, during the five years of the board’s activities, Californians gathered up all the papers they could to prove to the gentlemen of the board that they owned the land they had been living on for so many years. They looked into their leather trunks for original grants from Mexican governors. They called upon their friends and relatives to testify to long residence and to the number of their cattle. They went to Yankee lawyers for help. They sent to the Surveyor General’s Office in San Francisco for copies of the archives files relating to particular ranches. They made journeys and drew upon their slender fund of cash. They sometimes mortgaged their lands and their futures or conveyed “undivided” interests to their attorneys.”

Seventeen years is the average time it takes for a landowner to have their claim finally resolved by the courts or, in a handful of cases, Congress. Again from Land in California:

“As a result of these delays, rancho land was not salable, squatters came in like locusts, and the owners’ funds and resources went to lawyers and lenders. Most claimants were bankrupted in the process of getting clear titles. Some chose to sell out to speculators and sharpers. It was a ruinous period for Spanish Californians.”

TOP PHOTO: “El Toro Rancho,” California State Archives Exhibits, accessed December 31, 2019, http://exhibits.sos.ca.gov/items/show/11158.