California writers have created a rich tradition of social protest novels, beginning with John Rollin Ridge’s The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Muiretta: The Celebrated California Bandit, an 1854 novel that decries the treatment of Mexicans in Gold Rush California. Ridge’s novel is one of the first written by a Native American writer and is but loosely based on local bandit lore. Later social novels are often more attentive to the events of California history.

The best of these novels seize a historical moment to protest social conditions, reimagining history as fiction. Such novels haven’t always been effective in creating social change. A dispirited Helen Hunt Jackson lamented that her critique of the shameful American treatment toward Southern California Native Americans in her 1884 novel Ramona might have been more potent told as a children’s story. But social novels remind us of the perennial challenges that social injustices present. That is, they remind us what is at stake in the Golden State, which is sometimes the land itself.

Joaquin Miller chronicles the unconscionable treatment of California native people well before Jackson takes up her pen. His loosely autobiographical 1873 novel Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History draws upon Miller’s own experiences of strife between American miners and native people in the Shasta region.

When miners stream into the region during the 1850s, they disrupt the environment, including the natural resources that supported indigenous people for centuries. Miller writes:

“There are two hundred thousand men, the best and the bravest men in the world, wasting the best years of their lives getting out this gold. They are turning over the mountains, destroying the forests, and filling up the rivers.”

The story of American expansion into California threatens not only native peoples but also the beauty and wonder of the natural environment, a recurring motif of many California protest novels.

This same bonanza spirit of the Gold Rush animates Frank Norris’ 1902 novel, The Octopus, which seizes on the story of the Mussel Slough Tragedy, an 1880 gunfight between Central Valley settlers and representatives of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

The Southern Pacific seeks to sell to settlers land granted to the railroad by the federal government in order to encourage expansion and fuel greater development. The railroad prices its parcels higher than settlers—many of them land speculators styling themselves as hearty Jeffersonian farmers—think they should pay.

The event inspires five novels, but Norris’ is the best, offering the most unsparing treatment of everyone involved. Norris attempts to hew close to the history of the tragedy rather than replicate the myth of gritty pioneer settlers pitted against the railroad octopus. What Norris reminds us is that human beings in capitalist competition too often overlook the costs to the non-human world, in this case, “the whole gigantic sweep of the San Joaquin. . . .”

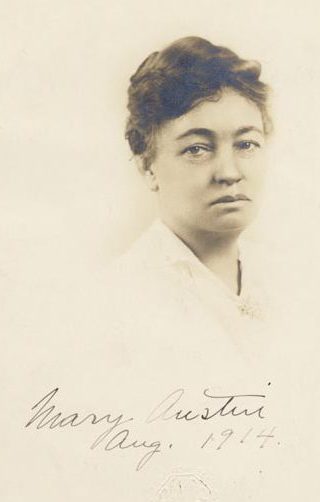

Mary Austin sees a similar problem in how Los Angeles appropriates water from the Owens Valley east of the Sierra, turning a desert into a paradise and making millions for speculators and developers. In her 1917 novel The Ford, she draws on this history in order to show that the locals, thanks to their “invincible rurality” and desire to “get in,” wind up sharing the same bonanza-bred values as the speculators who exploit them. And not only do they risk homes and livelihoods through their failure to successfully compete with well-heeled capitalists, they lay waste to the natural world that surrounds them.

Many other California writers contribute to the rich tradition of California social novels, among them are María Amparo Ruiz De Burton, whose 1885 novel The Squatter and the Don tells the story of contested property rights from a Californio viewpoint, and Upton Sinclair’s 1923 novel, Oil, the story of the damage done by Southern California wildcatting.

John Steinbeck’s 1939 epic The Grapes of Wrath chronicles the story of the Joad family, who flee dustbowl Oklahoma for the imagined paradise of California, only to find their hopes dashed among iconic images of bounty — a scathing indictment of American institutions that leaves many vulnerable people helpless against the ravages of the depression.

________

Terry Beers is professor of English at Santa Clara University. He has served as the general editor of the California Legacy Series of books, co-published by SCU and Heyday Books, and was the host of the “Your California Legacy” radio anthology, produced at KAZU Public Radio. He is the author or editor of five books on California literature, including The End of Eden: Agrarian Spaces and the Rise of the California Social Novel (U of Nevada P, 2018)