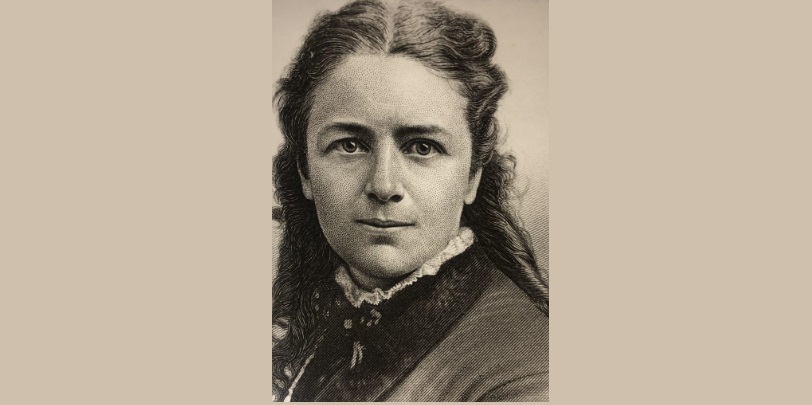

Laura de Force Gordon gives the first speech on suffrage in California at San Francisco’s Platt Hall on February 19, 1868. Her topic is “The Elective Franchise. Who Shall Vote?” Tickets are 25 cents. Several of the attendees become leaders in California’s suffrage movement, including Elizabeth Schenck and Emily Pitts Stevens.

With Schenck and Stevens, Gordon helps found the Women’s Suffrage Society in 1870, of which she later becomes president. She is credited by Susan B. Anthony with giving 100 speeches on suffrage in a single year.

“You can’t imagine how it delights my soul to find such an earnest, noble young woman possessed of powers oratorical,” says Anthony of Gordon.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1838, Gordon and her family become Christian spiritualists after the death of one of her brothers. Besides a belief in communication with the dead, spiritualists also believe in equality between men and women.

Gordon marries in 1862. She and her husband, Charles, a Scottish physician, come West and settle in San Joaquin County, where he practices medicine. The two divorce prior to 1878.

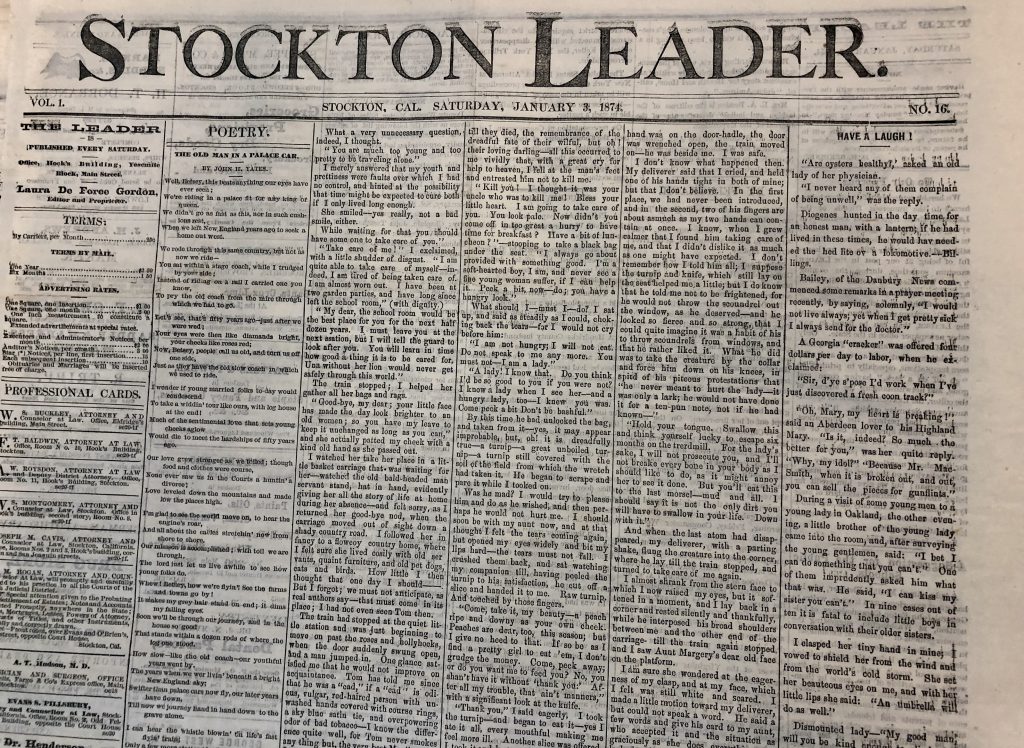

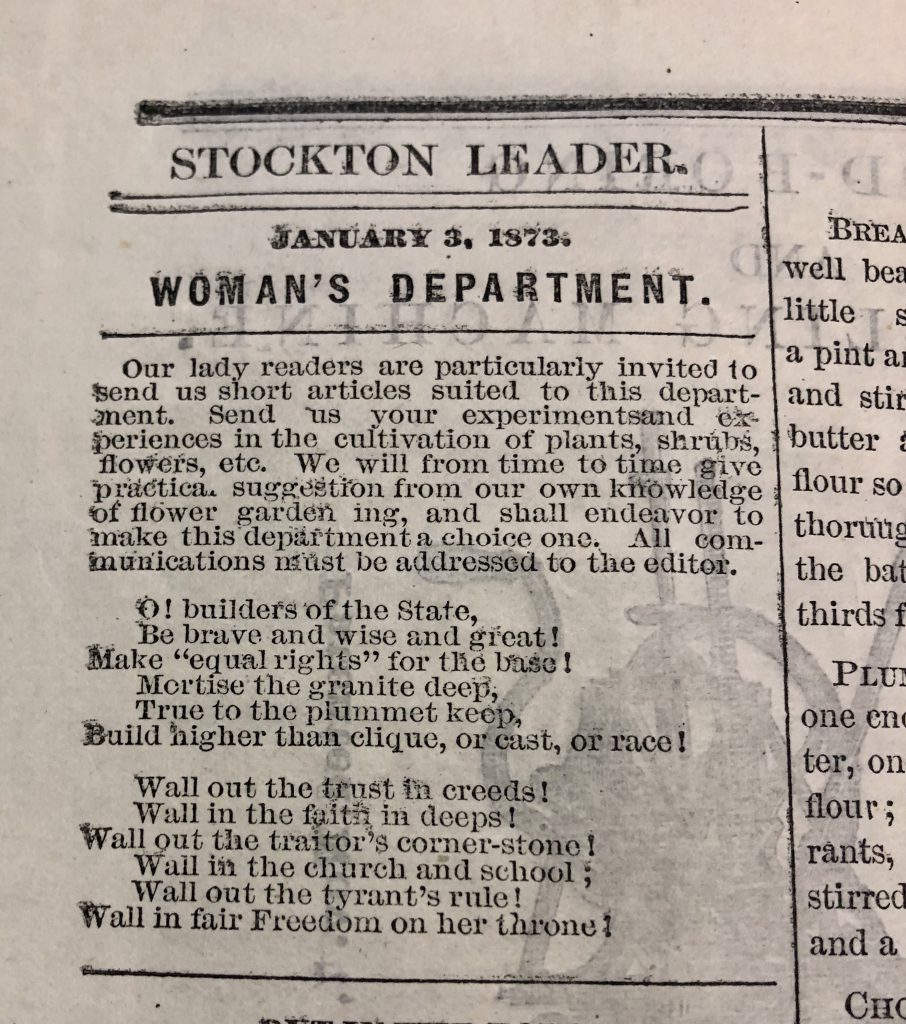

In 1874, Laura Gordon becomes publisher and editor of the Stockton Daily Leader and is credited with being the first woman in the world to publish and edit a daily newspaper.

Gordon works with fellow suffragist Clara Shortridge Foltz to successfully convince the Legislature and governor to allow women to practice law in January 1879. The two women also push the delegates to California’s Constitutional Convention of 1878 to include Article XX, Section 18, which reads:

“No person shall, on account of sex, be disqualified from entering upon or pursuing any lawful business, vocation, or profession.”

After passage of the legislation allowing women to practice law, Gordon and Foltz pay the $10 tuition for admission to the newly opened Hastings College of Law. On the third day of classes, they are asked to leave, in part because the school’s dean feels their “rustling skirts” disturb the male students. The women sue and convince the California Supreme Court to overturn their dismissal.

Although a champion of women’s rights, Gordon shares the views of many other Democrats of her time on Chinese immigrants to the West Coast, claiming they take jobs from white American citizens. The lawsuit against Hastings condemns the idea that Chinese men should be allowed to do anything white woman legally cannot.

In December 1879, Gordon and Foltz become the second and third women admitted to the California bar. Gordon hangs up her shingle in 1880 in San Francisco, becoming the first woman to address a jury in California and, in 1885, the second woman admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court.

She retires to her farm in Lodi in 1901, dying of pneumonia in 1907. She is buried at the Harmony Grove Cemetery in Lockeford.

Her death comes four years before women are granted the right to vote in California. “Woman suffrage is bound to come,” Gordon writes in 1896. “There has never been a time when so many men and women [take] so deep an interest in the subject and I am happy in the thought that our day of political freedom is so near.”