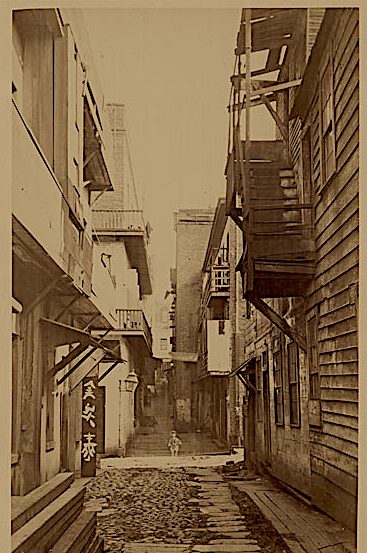

It is nearly dusk on December 14, 1933 when a Chinese teen named Jeung Gwai Ying flees from a hairdresser’s shop to a “safe house” in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Trafficked from China and forced into prostitution, Jeung seeks freedom for herself and her unborn child by running through Chinatown’s crowded streets to a squat building straddling a steep hill.

Jeung catches her breath at the entrance to 920 Sacramento Street, a brick house that serves as a door to freedom for thousands of enslaved and vulnerable girls. By now, it is nightfall and too late to turn back. Jeung has no other options. She pushes the doorbell once and then again. The doorkeeper peers through the grated window. She sees a young Chinese woman standing outside, her coat unbuttoned despite the cold, and swings open the heavy wood doors to let her in.

Two women come into the foyer from other parts of the house to meet her. One is a white woman in her sixties with a halo of silver hair, the other a bespectacled younger woman who speaks to Jeung in Cantonese. Listening carefully to the frantic girl’s pleas, the Chinese woman translates her words into English.

“Protect me!” cries Jeung.

The women are the home’s superintendent, Donaldina Cameron, and her longtime aide, Tien Fuh Wu. Together, they have worked for four decades to protect some of the city’s most scorned residents. They lead Jeung to an adjoining parlor, which has a comforting Chinese carpet on the floor and Cantonese hangings on the walls. The scent of Chinese food drifts through the house. Once they are seated, Wu and Cameron gently urge the teenager to tell them her story.

***

By the time of Jeung’s escape, Donaldina Cameron was one of the most famous women in California. A tall, auburn-haired woman with a Scottish lilt, she fascinated headline writers and the public alike for decades with her efforts on behalf of vulnerable girls and young women. Today, we’d call teens like Jeung who sought refuge at the home survivors of human trafficking.

The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown tells the story of Donaldina Cameron, Tien Fuh Wu, Jeung Gwai Ying, and many of the people involved with the home – white and Asian, women, and men.

I found it extraordinary how this small band of activists and survivors managed to disrupt the lucrative business of human trafficking between China and America for more than half a century. But while Cameron became famous for her work, I discovered that her Asian colleagues – such as Wu – were equally committed to their struggle against sex trafficking and slavery.

For decades, Cameron, Wu and others engaged in what they called “rescue work” – freeing women and girls from sex slavery and other forms of bondage. An unlikely pair, Cameron and Wu defied the conventions of their time and even, occasionally, broke laws to help other women gain their freedom. The home they ran at 920 Sacramento Street was one of the pioneering “rescue missions” in the United States, established more than a decade before the world’s first settlement house, Toynbee Hall in London’s East End, and 15 years before Jane Addams co-founded Hull House to offer aid to Chicago’s immigrants.

Both Cameron and Wu themselves were immigrants to the U.S. Cameron first arrived in San Francisco as a toddler aboard a steamship in 1871. Born in New Zealand to a Scottish family, she grew up on ranches in Central and Southern California. After a broken engagement, she returned to San Francisco in 1895, and worked at a Presbyterian Mission House in Chinatown as a sewing teacher. Wu, in turn, was sold as a child in China and brought to San Francisco to work as a child slave. Abused by her owners, she ended up at 902 Sacramento Street as a resident. Eventually, Wu became Cameron’s colleague and friend. Neither woman ever married or had children, but they shared a belief in the importance of their work.

Today, the barest outlines of Wu’s and many other resident’s stories fill a large bound ledger that still sits in a locked room on the home’s top floor. In careful, handwritten script, the book lists more than 800 names of women and girls who took refuge at the Mission Home from its founding in 1874 until January 1909. Nearly 1,000 more women’s names from the decades after that are recorded in the home’s case files. The story of how the home offered a refuge to so many vulnerable girls and women is contained within the lined pages of its ledger and offers tangible proof of the astonishing journeys these women made. The girls and women who passed through its doors escaped their bondage and found refuge in an ungainly brick house on Sacramento Street. Aided by Cameron, Wu, and others, these pioneers in the struggle against human trafficking helped touch off a fight for freedom that continues today.

***

Julia Flynn Siler is the author of The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown, published by Alfred A. Knopf in 2019 and a finalist for a California Book Award in nonfiction.

She will be in conversation with Helen Zia, the author of Last Boat From Shanghai, in a virtual event hosted by the California State Library Foundation on Thursday, March 18th. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com or follow her on Twitter @jsilerauthor.