Born enslaved in Georgia or Mississippi in 1818, Bridget “Biddy” Mason — with a nursing baby on her back and her two other young daughters beside her — walks behind her master’s wagon for most of the 2,000-mile journey to Salt Lake City, then to California, arriving at a new Mormon settlement in San Bernardino in 1851.

California has been admitted to the Union the year before as a free state, but in a move that belies the myth of western freedom, state lawmakers in 1852 approve a fugitive slave law that puts the liberties of many transported African Americans in jeopardy.

Even after the law lapses in 1855, Mason’s owner, Robert Smith who is the father of Mason’s two youngest daughters, continues to claim her as property. He decides to leave California for Texas, where slavery is still legal.

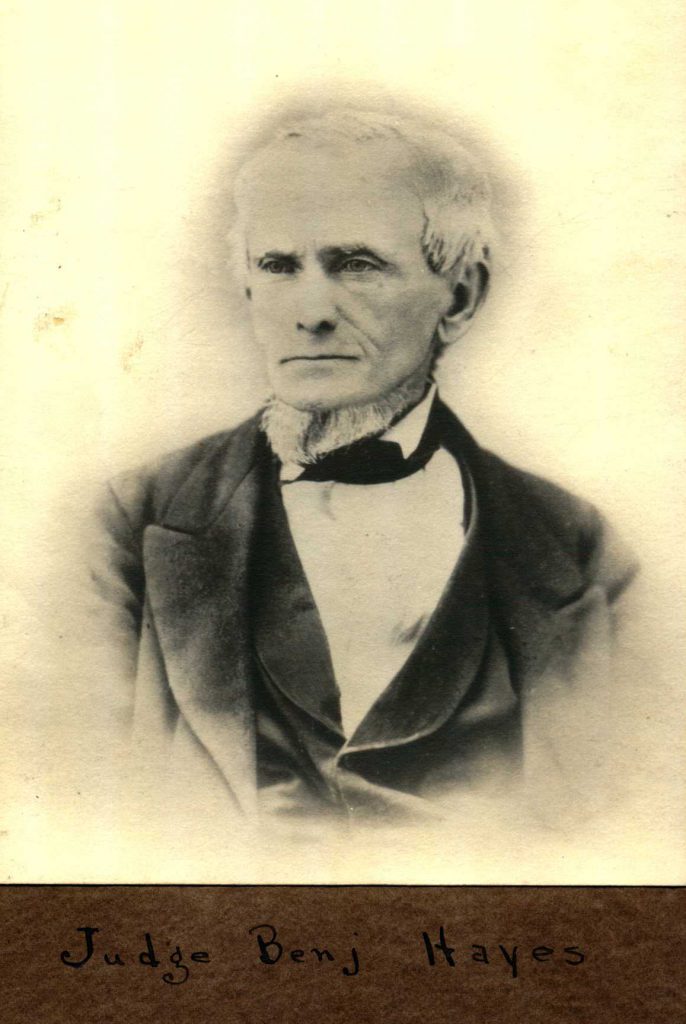

Biddy and a group of other enslaved people challenge Smith in court even though state law prohibits blacks from testifying against whites. Her lawyer tries to quit the case and admits under questioning from an angry Judge Benjamin Hayes that he has been bribed to do so. Fearing he will now be charged with bribery or worse, Smith leaves town.

In 1856, at the age of 37, Mason wins her freedom. Judge Hayes declares that she and the other enslaved people “should be left to their own pursuit of freedom and happiness.”

Seeking a fresh start, Mason and her family settle in Los Angeles, at the time a small town of 2,000 residents. A prominent local physician hires her. In her black medicine bag, Mason carries the papers Hays gives her attesting to her emancipation.

Working as a nurse and midwife, Mason diligently saves her money and uses $250 to buy a parcel on the outskirts of town between Broadway and Spring streets. The area later becomes the city’s downtown business district. The more real estate Mason buys and sells, the wealthier she gets.

In 1885, she deeds a portion of her remaining Spring Street property to her grandsons “for the sum of love and affection and ten dollars.” She signs with a flourished “X.” Mason has never learned to read or write. .

Much of Mason’s money is spent helping the less fortunate. She supports the poor in the city’s slums. She founds and pays the expenses of the city’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church, the oldest place of worship for African Americans in Los Angeles. She builds the city’s first school for black children.

Her home is refuge for those in need. She packs food baskets and took them to the local jail. When the Los Angeles River floods after heavy rains in 1884, leaving many Angelenos homeless, she buys groceries for the victims – black and white.

She is called “Aunt Biddy,” “Grandma Mason.” She says:

“If you hold your hand closed, nothing good can come in. The open hand is blessed, for it gives in abundance, even as it receives.”

When Biddy Mason dieds in 1891, she is buried in an unmarked grave. But 97 years later, city and church officials mark her grave with a tombstone. Biddy Mason Memorial Park now sits on the site of her original homestead, paying tribute to her remarkable life and contributions.

______

Steve and Susie Swatt are coauthors of Paving the Way: Women’s Struggle for Political Equality in California.