Between January and April of 1858, Northern California is rocked by the “case of the decade” – a determination of whether Archy Lee is allowed to live in California as a free man or be returned to Mississippi, a fugitive slave.

California enters the union as a free state in 1850. But even in 1857, Southerners still come to the Golden State with their “servants” in tow. Being a free state causes some of those “servants” to declare their freedom.

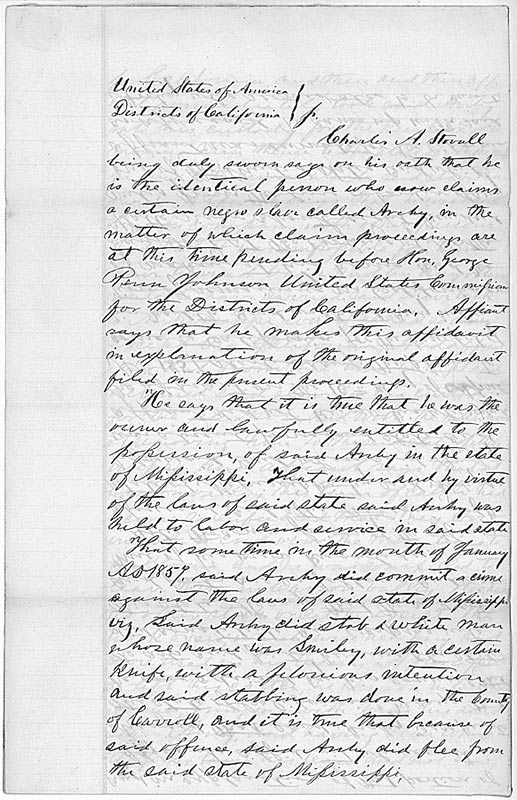

Such is the case when plantation owner Charles A. Stovall moves to California from Mississippi to try his luck in the gold fields. He brings along his slave, Archy Lee. Stovall has no luck finding gold and takes up teaching as a profession. Archy Lee considers himself a free man in California and sets up a barber shop in Sacramento.

In late 1857, Stovall decides to move back to Mississippi and orders Lee to return with him. Lee refuses. Stovall has him arrested in January 1858.

Over the next 14 weeks, there are two county district court cases, one State Supreme Court ruling, a refusal from a federal magistrate to hear the case, a kidnapping, and public protests before a final decision on Lee’s status is rendered.

Lee’s first trial is held in Sacramento County. The judge determines that Lee is a free man. Stovall and his lawyers make a personal appeal to the federal magistrate in San Francisco who bounces the case back to Sacramento County

According to newspaper accounts, during testimony at the Sacramento trial on January 23, 1858, Archy Lee says:

“I want it to come out right: I don’t want to go back to Mississippi.”

After Lee is declared a free man, local authorities promptly arrest him again.

Stovall has enlisted the help of California State Supreme Court Chief Justice David Terry, a pro-slavery Tennessee native who agrees to have the high court hear the case.

Two of the three judges of the California Supreme Court, Terry and Associate Justice (and first California governor) Peter Burnett, are pro-slavery but argue in their decision that the issue isn’t about the propriety of slavery but whether Stovall and Lee are residents of California or visitors. If Stovall is traveling through, as he claims, then he should be allowed to keep any “property” that he brought with him.

On February 11, to a packed court room that includes anti-slavery and pro-slavery supporters, Terry announces that Archy Lee is to be “given back” to Stovall. Burnett writes in the court’s opinion:

“This case has excited much interest and feeling, and gives rise to many questions of great delicacy. It is not so much the rights of the parties immediately concerned in this particular case, as the bearing of the decision upon our future relations with our sister States, that gives to the subject its greatest importance.”

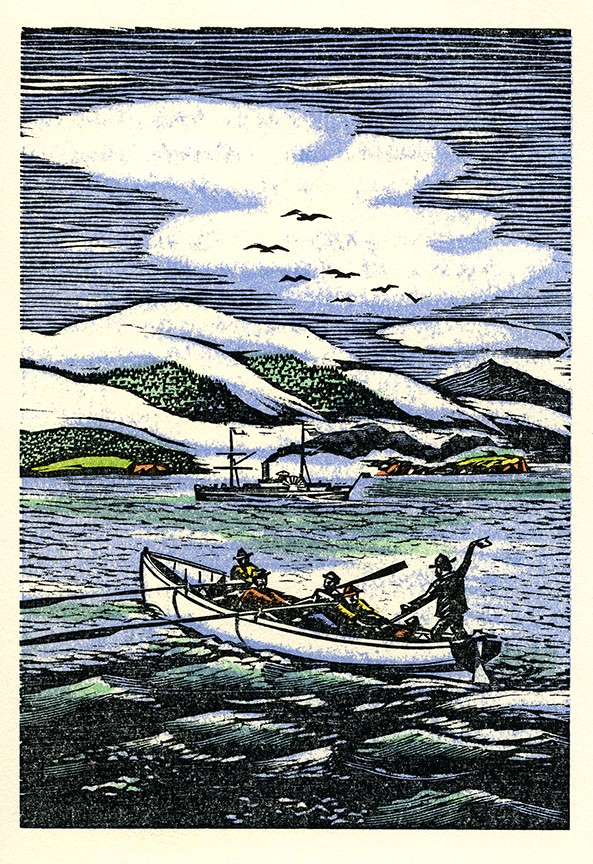

Stovall prepares to return to Mississippi with his “property.” Law enforcement officers are tipped off that Stovall intends to stow Lee aboard the Orizaba, set to depart San Francisco on March 5. Word leaks out and crowds gather on the wharf. Stovall’s supporters jeer as the ship pulls away from shore.

Onboard the vessel is a deputy sheriff and two of his assistants. A boat for the sheriff is attached to the Orizaba’s stern.

As the Orizaba nears Angel Island in the middle of San Francisco Bay, a rowboat with Stovall and the kidnapped Archy Lee pulls alongside. They board but after heated words and a scuffle, the Orizaba sails out through the Golden Gate, while Stovall and Lee return to shore with the sheriff.

Kidnapping charges leveled against Stovall by Lee’s supporters are rejected by the court. But Lee’s freedom is still in dispute. African Americans raise funds for Lee’s legal fees. Local papers criticize the tortuous logic of the State Supreme Court decision and encourage San Francisco judge T.W. Freelon to correct the injustice.

Freelon takes a look at the evidence and the law, and frees Lee — who is promptly arrested again to go on trial in federal court.

Reporters quote Lee as saying that he would rather die than return to slavery. Hundreds of people follow the U.S. marshals escorting Lee to the Merchants Exchange Building, which houses U.S. Commissioner George Pen Johnston – the same man who declined to hear the case months previously in Sacramento.

While Commissioner Johnston takes a 10-day break in the trial, Charles Stovall quietly departs San Francisco. Exactly why is unknown. One theory says he is about to be arrested for perjury. Another is that he’s been paid for Lee’s freedom and splits with the cash. The case continues in his absence in late March.

At one point in the proceedings, a member of Stovall’s legal team says Commissioner Johnston should place Lee — in fact, any African American — into bondage if a white declares him or her as property. Johnston finds that notion to be “monstrous” and on April 14, 1858, he renders his decision: Archy Lee is free.

After the ruling, Lee leaves for British Columbia as part of a migration of free Blacks looking for better opportunities free of the racial rancor in the United States. The Sacramento Daily Union reports in June that Lee is in Victoria, British Columbia.

The Pacific Appeal, a black weekly newspaper, reports in 1862 that Lee is working as a barber in Nevada.

There is no more news of Lee until November 7, 1873, when the Sacramento Record writes about the 15-year-old case. The article ends with this paragraph:

“Yesterday some boys were playing in the sand on the Yolo shore, opposite the mouth of the American River, when they discovered the body of a man buried in the sand, only his head protruding. They gave the alarm and the chap was resurrected and brought to the Station-house in this city. Arrived there he was found to be sick, and said he covered himself with the sand to keep warm. He was sent to the County Hospital. He had been camping there several months, a fact unknown until yesterday. He was the hero of the most exciting times of 15 years ago, the slave Archy Lee. His career in this State began here, and here it seems likely to end.”

TOP PHOTO: Archy Lee Court Document.