On January 21, 1913, the Oakland YWCA announces that the city’s own Julia Morgan — the most accomplished woman architect in the country — is going to design a $250,000 headquarters building for the organization.

It’s a big deal.

For Julia, this is the first of more than 30 buildings she designs for the YWCA over the next 20 years. For her sorority sister Grace Fisher, who is president of the local association, it marks the culmination of years of campaigning for a modern home befitting the oldest chapter of the YWCA in California. And for the city of Oakland, it marks the addition of another prominent building to the bustling downtown business and theater district. If all goes as planned, doors will open to the public in eight months.

Of course, nothing goes as planned. The YWCA has secured over $200,000 in pledges for the building – nearly all of the proposed budget for a monumental Beaux-Arts style institution – but collecting those pledges proves to be difficult. Further work will have to wait.

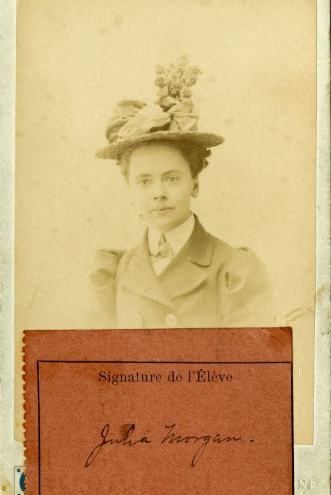

Julia Morgan Papers, Robert E. Kennedy Library, California Polytechnic State University

In the meantime, Julia turns her attention to other projects. She has several houses to design, including one for Elsie Drexler, a wealthy widow who has used her fortune to invest in commercial architecture in San Francisco and to support the children’s ward of San Francisco General Hospital. Mrs. Drexler has commissioned Julia to design a country respite in Woodside, south of the city.

The house, with its wood shingle exterior, shallow-pitched roofs featuring dramatic wide eave overhangs that shade large porches, and a pergola supported by columns of tree trunks, is a model of Arts and Crafts regionalism. Mountain Home, as the house is called, stands until 1999 when a man named Larry Ellison, founder of a technology company named Oracle, buys the property and has the house dismantled.

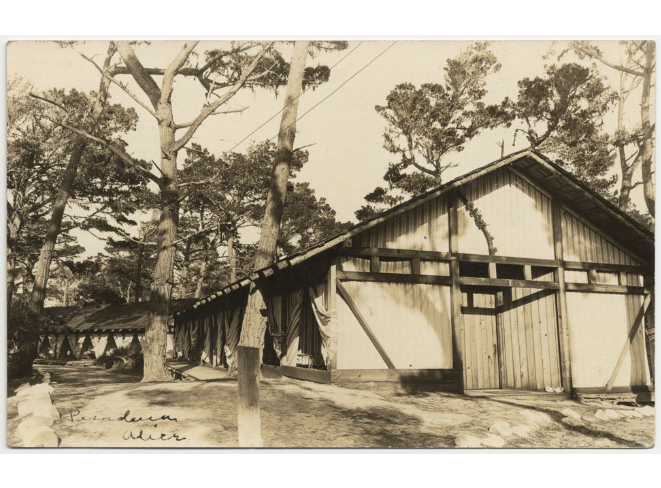

Julia then focuses on Asilomar, the first purpose-built conference center of the YWCA in the United States. Phoebe Hearst, a leading philanthropist in California who is also the widow of mining magnate and US Senator George Hearst, mother of media mogul William Randolph Hearst, and a longtime patron of Julia’s, has secured 30 acres on the Monterey Peninsula for this project and has donated $5,000 towards the first building on the site. That building, along with 10 tent houses Julia designed for an event Mrs. Hearst hosted at her estate, Hacienda del Pozo de Verona, in Pleasanton in 1912, must be ready for use on opening day of the Pacific Coast conference in August.

Like Mountain Home, Julia designs Asilomar in a rustic fashion, with a lot of wood inside and out; river stone-clad piers, fireplaces, and chimneys; and exposed structural elements that double as decoration. Over the next 15 years, Julia designs a dozen more buildings and structures all connected by curving pathways that follow the natural contours of the site. The whole project showcases Julia’s Beaux-Arts training in site planning and is the most significant collection of what future architectural critics dub the “Bay Tradition style”.

In March, the Oakland YWCA announces that the board has accepted plans for the $125,000 to $150,000 building – a notably smaller budget than originally anticipated. As is fitting for the most prominent women’s institution in Oakland at the time, the four-story reinforced concrete building finds inspiration in one of the most powerful women of Renaissance Italy, Marie de Medici.

Like Marie de Medici’s palace in Florence, the main façade is divided into three parts and features rustication, a series of arched windows, and a ribbon of windows at the top. In contrast to the Medici palace, Julia adds floral-themed glazed terra cotta tilework and a wrought iron balcony to create color and visual interest. The interior court, meanwhile, takes after Bramanti’s cloister at Santa Maria dela Pace and features uplifting verses from the Bible to nourish the young patrons’ spirits. The facility will have social, educational, recreational, cafeteria, and residential functions, but Julia has been busy scaling back the project on account of the smaller budget. Consequently, a pool will have to wait a few years.

Just days later, tragedy strikes. Julia’s brother Gardner “Sam” Morgan, a fire captain, is riding in the fire department’s roadster when a train collides with it, throwing Sam and the fire chief from the car. Sam suffers major head injuries and spends the next six months at Providence Hospital.

Despite the trauma Sam’s injury creates for Julia and her family, Julia’s work continues.

Her next job is a relatively small residential project for an old mentor, Mollie Conners. She is Julia’s high school mechanical drawing instructor who left teaching in the mid-1890s to publish a weekly women’s newspaper and become a leader in the state’s women’s suffrage movement. Julia joined the final campaign for the vote in 1911 and immediately registered as a Republican when the ballot measure passed — as one does when one’s close relative is a charter member of the Grand Old Party and served as a pall bearer at Abraham Lincoln’s funeral.

Miss Conner’s house is also a good distraction for Julia’s brother Avery, too. His mood has always swung in highs and lows, making it difficult for him to hold down a job, but he can chauffeur Julia to Miss Conner’s job site, which helps keeps his mind off Sam’s accident.

And then comes William Randolph Hearst. In June he publishes a full-spread article about the Los Angeles Examiner building he is having constructed on an entire city block in downtown Los Angeles. Julia is the principal architect of this monumental and ornate Mission revival building.

She has known Hearst for years through her work on the Greek Theater at UC Berkeley, which he commissioned, and through her work on his mother’s estate in Pleasanton. She also designed a mansion for Hearst in Sausalito in 1908, but only the retaining wall is ever built.

The Examiner building is the first commission that the client and architect complete together. The scale and scope of the project is good preparation for what will come a few years later when Hearst decides to build a “castle” in the Santa Lucia mountains above San Simeon.

The summer of 1913 is a busy one. Asilomar opens on time and with great fanfare in August. Residential commissions are approaching a dozen for the year. The Examiner Building is nearly ready for occupancy, though the decorative work will still take considerable time to finish. New commissions related to the Panama Pacific International Exposition, which will be held in San Francisco in 1915, are beginning. Most notably, a group of women in Alameda County have asked Julia to design a juvenile court building for all the anticipated runaway children who will be lured to the fair.

Finally, on September 17th, groundbreaking ceremonies for the YWCA take place. It is a bittersweet moment: Julia and her family are mourning the loss of Sam, who has finally succumbed to his injuries a couple of weeks earlier. The money for his funeral monument will go towards the design and construction of bronze gates for the Kings Daughters Home for Incurables, a hospital Julia has been designing incrementally for years.

But the groundbreaking itself is a joyous occasion and Grace Fisher is brimming with happiness as she turns over the first shovel of soil. The construction project has already generated more than 30 contracts and provides employment for more than 50 men.

When the YWCA’s doors open to the public 16 months later, the Oakland Tribune says the building stands as nothing less than “a triumph of architectural beauty—represents the best thought of a woman, Miss Julia Morgan, the well-known architect. It represents also one of the finest achievements of women on the coast…. a monument to woman’s ability, and a landmark expressing her sympathy for other women, her sense of responsibility, and her deepening love for all other women.”

***

Karen McNeill, Ph.D., is an expert of Julia Morgan. Her latest publication, “Julia Morgan in Paris,” will be available shortly in Julia Morgan: the Road to San Simeon. Dr. McNeill’s scholarship focuses on women and gender in the architectural profession as well as how Progressive Era women used the built environment to expand their roles in society as consumers, reformers, educators, and professionals. Her work has been supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Autry National Center, the Bancroft Library, and the University of California Humanities Research Institute. Karen has also taught history and architectural history at colleges and universities in the San Francisco Bay Area and has been involved in historic preservation, authoring several context statements for major surveys and successfully nominating a range of buildings to the National Register of Historic Places. She is currently Senior Family Historian at Ascent Private Capital Management of U.S. Bank and a trustee on the board of the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF).