On February 25, 1854, Gov. John Bigler ends California’s five-year game of musical capitals by signing legislation making Sacramento California’s permanent seat of government. Over the past five years, the capital has been in Monterey, San Jose, briefly Sacramento, Vallejo and — prior to Bigler’s signature –Benicia.

Lawmakers representing the Bay Area whaling port use myriad legislative strategies to defeat a move to Sacramento but can’t quite get it done.

Benicia is named after the wife of Californio landowner and state Sen. Mariano Vallejo.It seems downright luxurious compared to the capital’s previous location, 156 acres donated by the same Mariano Vallejo. Benicia has a new brick town hall with columned portico and interior pillars made of old ships’ masts. Its nightlife includes a hotel saloon with two pianos that stays open 24 hours a day.

Vallejo donates the 156 acres to create a capitol city of “Eureka.” There’s supposed to be a Capitol, schools, botanical garden, hospital and prison. Vallejo even offers to kick in $370,000 of the construction costs. The Legislature sees a good deal for the cash-strapped state and approves the plan but changes the city’s name from Eureka to Vallejo.

A special commission lays out the new city, placing the capitol, the governor’s home, a university and several other public institutions on a hill “above the secure and commodious harbor of Napa Bay, from which, on a clear day might be seen the city and shipping of San Francisco.” The asylum is sited nearby with the penitentiary on a prominent bluff along the Carquinez Straits, to serve as a warning to “rascals” on their way to the goldfields.

But what greets lawmakers the following year when they convene in Vallejo for their third session on January 5, 1852 isn’t a new capital — it’s chaos. Reports the Sacramento Daily Union:

“The furniture, fixtures etc. are not yet in their places; many of them have not yet arrived in Vallejo…no printing materials in town… few or none of the buildings in town finished…music of the saw and hammer heard night and day.”

In his 1888 History of California, Hubert Howe Bancroft writes:

“The $125,000 capitol so far was a rather insignificant two-story building with a drinking saloon and a skittle-alley in the basement – the third house, as it was ironically called.”

Accommodations for 50 members of the Legislature are berths on the Empire, a steamer that seizes the opportunity to become a pricey floating hotel. While the new capitol is being built, the Legislature meets in a leaky building, using barrels for seats and boxes for desks. After only 11 days, miffed lawmakers vote to move to Sacramento for the remainder of the session, which ends in May. When they reconvene the following January, construction will be completed on what they still intend to be California’s permanent capital of Vallejo.

In January 1853, more of Vallejo is completed but the weather is miserable. A flood has just inundated Sacramento. Vallejo, the lawmaker and landowner, wants to be released from his contract. Lawmakers face a Hobson’s Choice: Stay in the uncomfortable, unfinished city or return to Sacramento, still sifting through the wrack and ruin of the flood. That’s when Benicia starts looking pretty good.

(The restored capitol in Benicia is now a state historic park and the only pre-Sacramento capitol still standing.)

But Bigler wants the capital to be Sacramento. And so does Sacramento, which offers free land, fireproof vaults for state records and free moving passes if Benicia is abandoned. Benicia legislators and lawmakers from other parts of the state block the move. Gov. Bigler turns up the political pressre. Feb

In his January 4 message to the Legislature, Bigler tells lawmakers:

“Although deeply impressed with the importance as well as the necessity of economizing in every department of the state government, I feel it incumbent upon me to direct your attention to the insecure condition of the public archives. The entire public records as well as the state library now numbering about 4,000 volumes are kept in fragile frame buildings, without fireproof vaults or safes. The public records are now invaluable and if destroyed could not be replaced and their loss would involve the state and individuals in serious difficulties.”

Two days later, Bigler forwards the Legislature a letter from State Treasurer Selden McMeans saying the “tenement” he occupies in Benicia and the “iron safe in which most of the valuable effects of the officer are deposited” is “entirely insecure.” The Democratic governor forwards correspondence from Sacramento’s mayor and city council that provides a solution to this “insecurity.”

In the letter, Sacramento offers its new courthouse for the Legislature’s use as well as fireproof vaults to store public monies and records. Sacramento also offers the state a public square between I and J Streets and Ninth and Tenth Streets as a site for a permanent capitol.

The 34-member Senate and the 80-member Assembly refer the governor’s correspondence and the “removal’ issue to special committees. There are enough votes for the move to Sacramento in the Assembly; the Senate tilts toward staying in Benicia.

A three-member majority of the Assembly committee charged with examining the “Removal Question” reports on January 13 that the capital should be relocated to Sacramento. Despite enduring catastrophic floods and fires during the past 12 months, Sacramento’s citizenry – with “dauntless energy” – has created “a city, in substantial wealth, commerce and population, the second in California.”

The majority – Assembly members S.A. Ballou, John Musser and W.S. Letcher – hail from El Dorado, Trinity and Santa Clara, respectively. Sacramento has built “several hundred brick buildings, all of them substantial, many of them magnificent,” the majority report continues. The city’s “raised thoroughfares (are) substantially planked” and a new levee has been built. All of which “attest the confidence of the citizens in the permanence of their location and the determination and perseverance with which they have met and overcome the unparalleled combination of disaster and misfortune with which that ill-fated city was visited in the autumn and winter of 1852 and 1853.” Sacramento is a convenient crossroads as well, the Assemblymen write:

“Nine lines of splendid stages penetrate to every important point in the interior. Magnificent steamers plying daily to San Francisco and to cities and towns on the Sacramento and its tributaries, present facilities for speedy communication between the representative and his constituents, unequalled at any other place in the state. The fact that Sacramento affords daily communication with a population of 150,000 in itself establishes the proposition that the city is one of the great business centers of our state. It is also the center of an extensive system of telegraphic communication, either already in operation or in a state of forwardness, and is destined at no distant day, by its general advantages and geographical position, the center of an extensive system of railroads.”

Benicia has no law library and no printing plant, the majority committee notes, and is difficult to get to. “The time lost at the last session of the Legislature in consequence of the want of a quorum to do business cost the people about $50,000,” the majority report says. Assemblymen H.B. Kellogg of Yuba County and R.C. Whitman of Solano County, where Benicia is located, take a dimmer view in their minority report:

“The enterprise and dauntless energy of the citizens of Sacramento are worthy of all praise but it is somewhat to be doubted if even the dauntless energy aforesaid could, in the course of human events, have created a population only the second in California, unless by some means of propagation not generally known or commonly understood. While the disasters by fire and flood to which Sacramento has been subjected are to be lamented, it may very properly be doubted whether the fact, as stated in the majority report of this committee, that Sacramento has within 12 months been at once a desert and a swamp, is the most cogent of arguments for the removal of the state Capital to that place at the present time.”

On January 18, the special Senate committee issues a majority report favoring the move to Sacramento and two minority reports – one opposing the move and another favoring a post July 1 move, two months after the 1854 session concludes. After several abortive motions to table and an attempt to substitute “San Jose” for “Sacramento,” the Assembly passes a February 3 resolution on a vote of 39 to 35 saying that the remainder of the session, beginning February 9, be held in Sacramento. Staying in Benicia remains the choice of a majority of the 34-member Senate.

When the Assembly resolution arrives in the upper house, Sen. Charles Leake of Calaveras County moves to lay it on the table. The motion fails. Sen. Henry Crabb of Stockton proffers an amendment to replace “Sacramento” with “Stockton.” That fails. A motion to put the bill over as a special order of business for the following day fails. Sen. B.C. Whiting of Santa Cruz seeks an amendment to strike “Sacramento;’ and replace it with “San Francisco.” That fails. The question is finally called and the resolution defeated, 23 to 10. The Senate’s Sacramento supporters seek reconsideration.

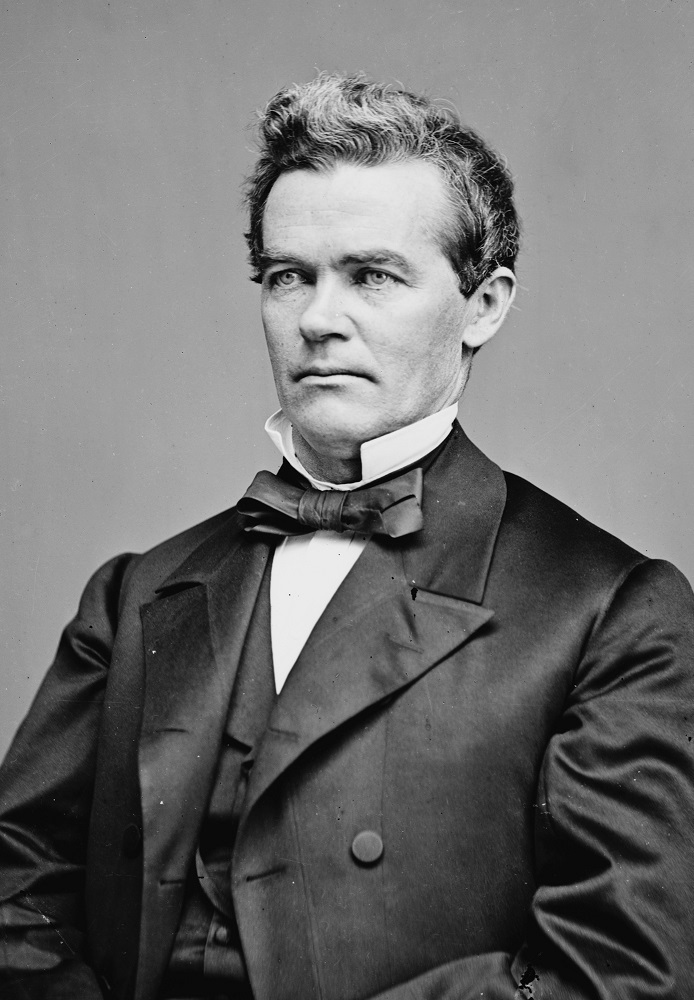

In the meantime, Sen. Amos Parmalee Catlin tells his Sacramento constituents to cease their lobbying efforts, which he says have done nothing but inflame the opposition. Catlin, a native New Yorker who came to the gold fields in 1849, assures Sacramentans the effort to move the capital is far from dead.

On February 7, the 31-year-old lawyer serves notice he’ll introduce legislation designating Sacramento as California’s permanent capital, which he does on February 9.

It’s Friday, February 17. Catlin sees an opening. Three “no” votes on Sacramento are absent. Catlin takes up his bill. Opponents move to adjourn. Motion fails – 14 to 12. Sen. William Lyons of Nevada County moves to send the bill back to committee. Hi motion fails.

Catlin opens on his bill, makes the case for Sacramento. Opponents of Catlin’s bill again move to adjourn. The motion fails, as does a subsequent one to lay the bill on the table. Finally, the question is called and Catlin’s bill passes, 15 to 12. One of the “aye” votes is Whiting who previously had tried to substitute San Francisco as the capital. Opponents win reconsideration for the following day, however.

“The measure was assailed with more violence than argument,” writes Oscar T. Shuck in his 1889 book, Bench and Bar in California: History, Anecdotes, Reminiscences:

On Saturday, Crabb of Stockton seeks reconsideration of the previous day’s vote – and narrowly wins it, 13 to 12. Lyons makes the same motion he did Friday. It’s defeated, 12 to 11. Sen. Charles Bryan of Yuba County moves to indefinitely postpone action on Catlin’s bill. His motion fails, 15 to 10. Sen. Royal Sprague of Shasta County moves to postpone hearing the bill until April. That motion is defeated as is another motion to send the bill back to committee, another motion to adjourn and yet another motion to put off consideration of the bill until March 15.

Finally, Catlin succeeds in sending his bill to the Assembly on a 13 to 11 vote. The shenanigans begin again.

When Catlin’s bill is on First Reading in the Assembly, a motion is made to reject it. That fails on a 35 to 32 vote. On Thursday February 23, Assemblyman John Conness of El Dorado County brings up Catlin’s bill for second reading. Opponents try to send the bill back to committee. Conness moves to refer it to the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds with a requirement they report back the following day.

The committee dutifully reports back on the 24th, urging passage. Opponents offer various amendments — have the act take effect 40 days after it passes, substitute Stockton for Sacramento, substitute Santa Rosa for Sacramento, substitute Marysville for Sacramento, and prevent any lawmakers from collecting per diem during the interim between adjourning in Benicia and moving to Sacramento. All are defeated and, like the Assembly’s own resolution before, Catlin’s bill is approved on a 39 to 35 vote. The Senate concurs the following day, 16 to 4. Shuck footnotes:

“The people of Sacramento did not receive the intelligence until after the bill had passed and were much astonished at so suddenly receiving the boon which they supposed was irrevocably lost and for which they had made a four years’ struggle.”

With Bigler’s signature on Catlin’s bill, February 26 is the last day the Legislature can legally meet in Benicia. So it adjourns and reconvenes Wednesday, March 1 in Sacramento’s 60-foot by 80-foot brick courthouse. The courthouse and 12 other city blocks rebuilt after the city’s 1852 fire are again consumed by flame in July but a new courthouse is built to welcome lawmakers back for their sixth session in January 1855.