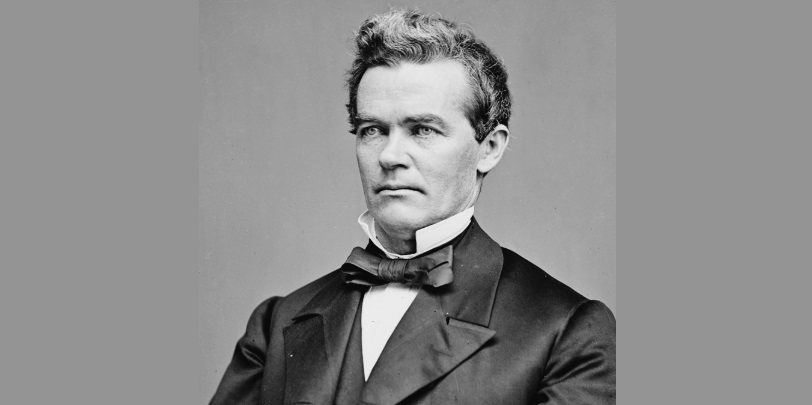

On February 10, 1863, state lawmakers choose Assemblyman John Conness, a strong opponent of slavery, as California’s U.S. Senator, succeeding his slain political mentor and ally, David Broderick of San Francisco. Support of Chinese immigration in the face of strong public opposition to it ends Conness’ political career in 1869 but not before he convinces Abraham Lincoln to sign legislation protecting Yosemite from development.

Born in Abbey, Ireland in 1821, Conness comes to America at age 15. The siren song of California gold lures him into leaving New York City in 1849 and coming west to seek his fortune. He settles in Georgetown in El Dorado County, making more money running a mercantile store than he does prospecting. Slavery is what gives him the political bug, says Conness in 1904:

“It was never my purpose to seek public office or public life and until later when there were such efforts to ally California with proslavery, I never dreamed of, nor had ambition to fill public place.”

He wins an Assembly seat in 1853, tying his political fortunes to Broderick, another son of Irish immigrants as well as the head of a powerful San Francisco political machine. Conness’s political career waxes and then wanes along with Broderick’s. But after Broderick is killed in a 1859 slavery-related duel with David Terry, former chief justice of the state supreme court, Conness becomes the head of Broderick’s anti-slavery “Union Democrats.” Cutting a deal with the anti-slavery Republicans secures Conness his Senate seat. He serves only one six-year term then moves to Boston where he dies almost 40 years later at the age of 87.

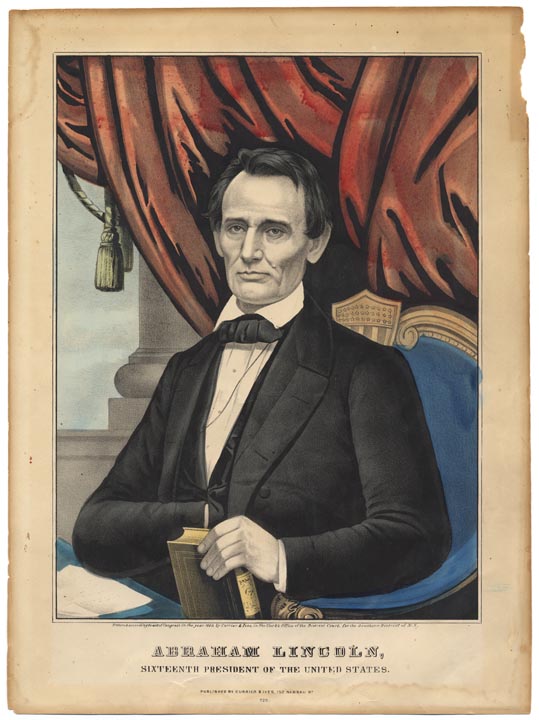

Those six years in the US Senate span the ending of the Civil War and the first turbulent years of Reconstruction. In Congress, Conness remains a vocal critic of slavery and a backer of President Abraham Lincoln’s war efforts as a means to end it. On November 13, 1863, Conness meets with Lincoln and offers the Republican president a cane that Broderick had given to him. Lincoln gratefully accepts it. Conness doesn’t introduce much legislation while a senator but he does carry a bill granting the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove to California. In his May 17, 1864 speech to his colleagues, Conness says:

“This bill proposes to make a grant of certain premises located in the Sierra Nevada mountains, in the State of California, that are for all public purposes worthless but which constitute, perhaps, some of the greatest wonders of the world…. The object and purpose is to make a grant to the state, on the stipulation contained in the bill that the property shall be inalienable forever, and preserved and improved as a place of public resort. The necessity of taking early possession and care of these great wonders can easily be seen and understood.”

It’s the first such land use measure in US history. Lincoln signs the bill on June 30, 1864. Conness serves as a pallbearer at the assassinated president’s funeral in April 1865.

During Reconstruction, California’s anti-Chinese sentiment sharply increases. The belief is that Chinese workers compete with white workers for jobs and the willingness of the Chinese to work for less pay drives down wages for all other workers. Conness opposes Chinese workers being brought to California as forced labor through “coolie contracts” but still supports Chinese immigration. Chinese immigrants are a necessary part of the state’s economy, Conness says:

“They are a docile, industrious people, and they are now passing into other branches of industry and labor. They are found employed as servants in a great many families and in the kitchens of hotels. They are found as farm hands in the fields; and latterly they are employed by thousands (to build the Central Pacific Railroad.)”

His unpopular views about the Chinese, the unraveling of his alliance with the Republicans and the collapse of the Union Democrats as a political party all conspire to end Conness’ political life in 1869.