“The California Gold Rush was a “universal mass trespass that shortly created laws to legitimize itself.”

— Wallace Stegner

Some states are conceived in slavery. California is birthed in genocide.

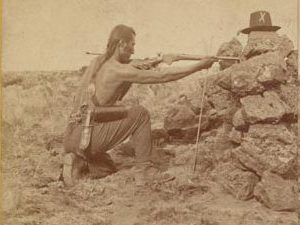

Fewer than four months after California is admitted to the Union as a “free state,” meaning only that slavery isn’t legal within its borders, the state’s first governor in a major speech describes “the Indian foe” and calls the native people — rightful owners of the land and resources of the new state — robbers and savages. He then declares:

“[A] war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct….” The speech, given by Gov. Peter Burnett on January 6, 1851, is his State of the State address.

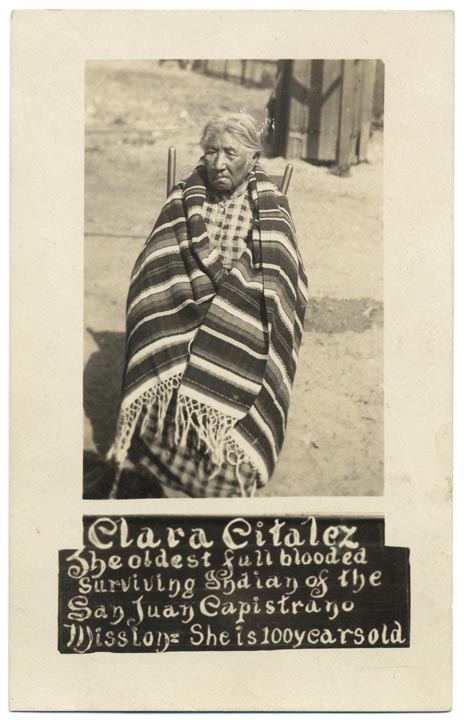

Between first European “contact” (that we know of) in 1542, until the end of the California Mission period in 1834, the population of Native Californians drops from 350,000 to 150,000. The causes are many: European diseases to which the Indians have no immunity; abuse at the hands of some of the Spanish padres and soldiers; and suicides wrung of despair.

From 1834 until 1880, however, the native population plummets far more dramatically, from 150,000 to 18,000. In all, Native Californians suffer an almost 95 percent loss of population by 1880.

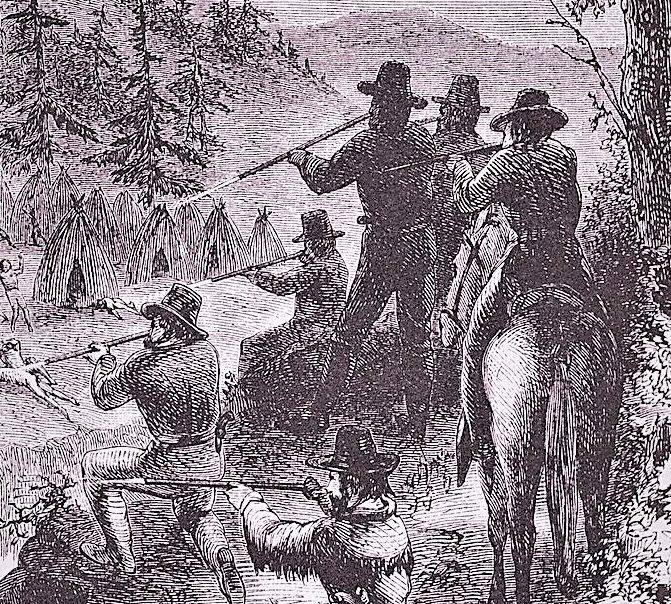

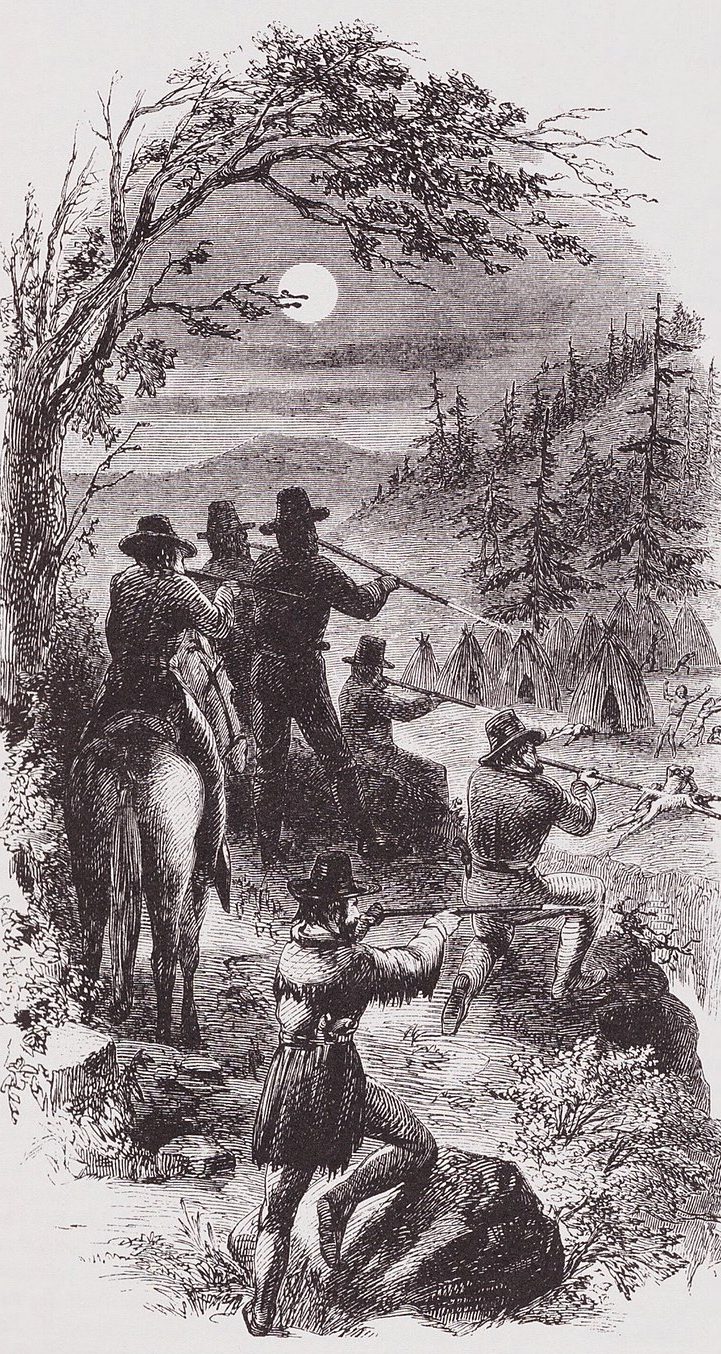

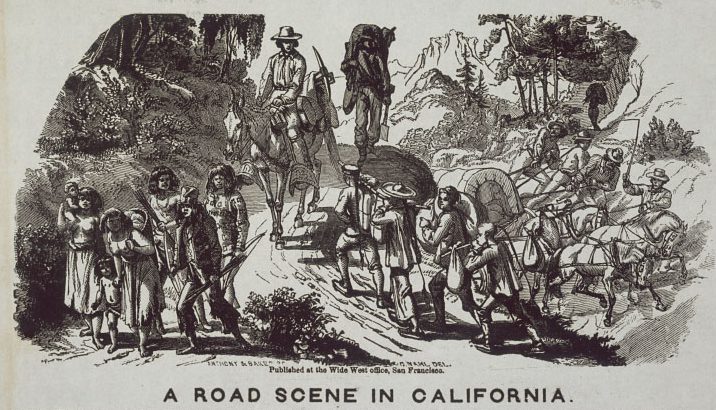

During 1834 to 1880, the principal cause of the population collapse is the murder of Indians by the mostly white gold-seekers and settlers. Indian hunting is sport. But it has the added benefit of ridding the state of those who might assert their superior land rights, rights the United States would be obliged to honor under international law.

A brief summary of events in California’s colonization is in order. Spain claims California in 1542, but doesn’t begin to colonize the land until 1769, when the first mission is established at San Diego. In all, the Spanish found 21 missions, from San Diego to Sonoma.

In 1821, Mexico wins independence from Spain and in 1834 Mexico seizes virtually all mission lands from the Catholic Church, and begins granting them to private individuals.

More than 600 of these vast land grants are later proved valid in American courts. In 1846, the United States defeats Mexico in the Mexican War, and establishes some modicum of authority here.

On January 24, 1848 gold is discovered at Coloma and, nine days later in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico cedes to the United States New Mexico, most of Arizona and large portions of Colorado and Wyoming. The United States also receives what will eventually become the states of Utah, Nevada, and California.

Little changes in California though, until the fall of 1848 when President James K. Polk, in his State of the Union Address, announces that reports of gold in California are true, and all are welcome to come and take it. Hundreds of thousands come — and take. Jim Holliday aptly titles his monumental book on this time, The World Rushed In.

All assume, or pretend to assume, that the United States is the owner of the lands and waters in the Sierras where gold is discovered. The assumption ignores the well-established international-law principle of “aboriginal rights,” which says that indigenous peoples hold rights in their lands superior to any rights of a conqueror. Even in 1849, the United States Supreme Court has recognized the principle many times.

Virtually all of the Sacramento Valley, and all the coastal land in California from below Fort Ross in the north to the Mexican border, has been placed into private ownership through land grants from the Mexican government. These vast holdings are the subject of decades of litigation between men claiming to have been granted land by the prior sovereigns, and the United States, which takes possession of the land if a claims by the private owner fails.

Forgotten in the process is that a California native has a prior, and superior right to the land under international law.

In the 1850s, Serranus Hastings is a prominent promoter and financier of Indian-hunting expeditions. During this period he is also the first Chief Justice of California as well as the state’s third Attorney General from 1852 to 1854.

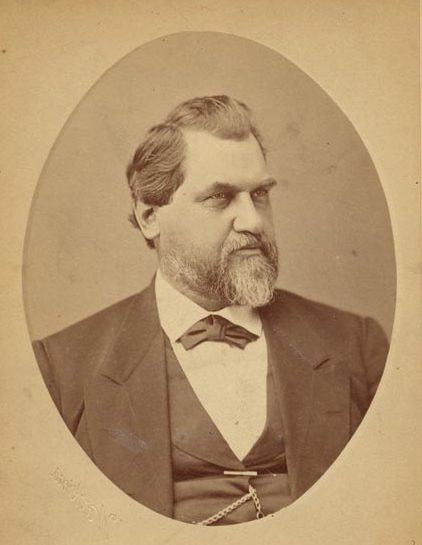

During the Civil War, Leland Stanford solicits volunteers for quasi-military campaigns against California Indians. As governor of California from 1861 to 1863, he signs into law appropriation bills to finance those killing expeditions.

Stanford’s favorite Indian killer is Major James D. Savage, leader of a militia called the “Mariposa Battalion.”

Facilitated by the successes of extermination, both Hastings and Stanford acquire vast tracts of land and make fortunes in real estate. Their ability to acquire land titles is facilitated by their massacre of the rightful claimants.

University of California at Los Angeles Professor Benjamin Madley writes in his sobering An American Genocide, that Leland Stanford and Serranus Hastings “help to facilitate genocide . . .”

Both Stanford and Hastings also found prestigious institutions of education still bearing their names: Stanford University and Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, the oldest law school in the state and part of the University of California system.

A college at Yale University no longer bears the name of John C. Calhoun, in response to mostly student objections that Calhoun owned slaves and was an ardent and eloquent proponent of slavery. At Harvard Law School and elsewhere, names of slave-holding patrons have disappeared.

None of the states formed from the territory gotten from Mexico by the 1848 treaty become slave states. Not being a slave state does not eliminate prejudice, however.

The Foreign Miners Tax is one example from early in California’s statehood of efforts to disadvantage Chinese and other immigrants.

James D. Phelan, US Senator from California from 1915 to 1921, uses the slogan “Keep California White” in his unsuccessful 1920 re-election bid.

In 2017, the University of San Francisco changes James D. Phelan Hall to Burl Toler Hall. Toler is the co-captain of USF’s famous 1951 football team and the first African-American official in a major American professional sports league.

Throughout the United States today, people clamor to remove the names of persons who supported slavery. In America’s ever-evolving relations with race, we ride a new wave of sensibility.

A moment’s reflection reveals the extent that our streets, schools, buildings – even our nation’s capital – are named for slaveholders. In the rising crest of this new sensibility, where lies genocide?

______

John Briscoe, winner of the 2020 Oscar Lewis Award in Western History, is a poet, author, and international lawyer.

He is a Distinguished Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, which will publish his oral history late this year, and is president of the San Francisco Historical Society.