![President Polk [Library of Congress CALL NUMBER DAG no. 391]](https://cal170.library.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/800px-James_Polk_restored.jpg)

When President James K. Polk receives news that his emissary has signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, it’s doubtful he imagines inebriates in an elephant suit tumbling into a Philadelphia orchestra pit. But it’s likely Polk knows his State of the Union address he’ll deliver later that year will strike thousands with gold fever, sending them scrambling to “go see the elephant” in the new west.

Nicholas P. Trist, Polk’s Chief Clerk in the State Department, signs the treaty of “Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement” despite his boss’s opposition. The agreement with Mexico includes a land purchase that adds 525,000 square miles to U.S. territory, an area that would later encompass seven western states, including California. For $15 million Trist brings home the roses and the bonbons: Yellowstone, Yosemite, the Grand Canyon and the Grand Tetons, Yet Polk is disappointed. He wants more. He soon gets it, tied with an auriferous ribbon.

The Gold Rush starts as a trickle. San Francisco newspapers promptly report James Marshall’s January 24, 1848 discovery, but few people hurry to pack the donkey. The public thinks the story is a hoax. Then Sam Brannan, a brash excommunicated Mormon and California’s first millionaire, steps off the San Francisco ferry fresh from the Coloma gold fields. He holds aloft a quinine bottle filled with that precious mineral of which coins and Guggenheim toilets are made.

A few months later, President Polk confirms: “…accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district…” With Polk’s bullish Bonanza!, all hell breaks loose…and not a few elephants.

During the Gold Rush, “seeing the elephant” has two decidedly different meanings. On the one hand, “I’m going to see the elephant” conveys a prospector’s anticipation of an attainable windfall. On the other, “I have seen the elephant” is a world-weary admission that golden expectations have washed out like dirt in Reality’s sluice. A few years later, battle-scared veterans of the Civil War employ the latter usage as an expression of disillusionment.

Historians at one time attribute the phrase to an 1820’s pratfall in a Philadelphia theater. As noted by the Department of Arkansas Heritage, “The performance required an elephant onstage (in this case, two men in a single costume) for a long duration.” Awaiting their cue, the bored actors swig smuggled spirits inside the wrinkled, grey suit. When finally prodded, the pantomime pachyderm vandykes across the veldt into the orchestra pit, inspiring a wag in the audience to stand and declare: “I’ve seen the elephant!”

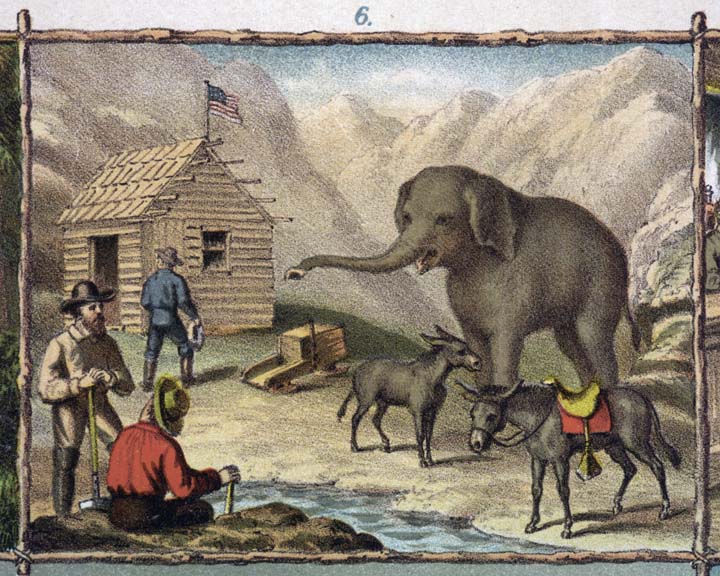

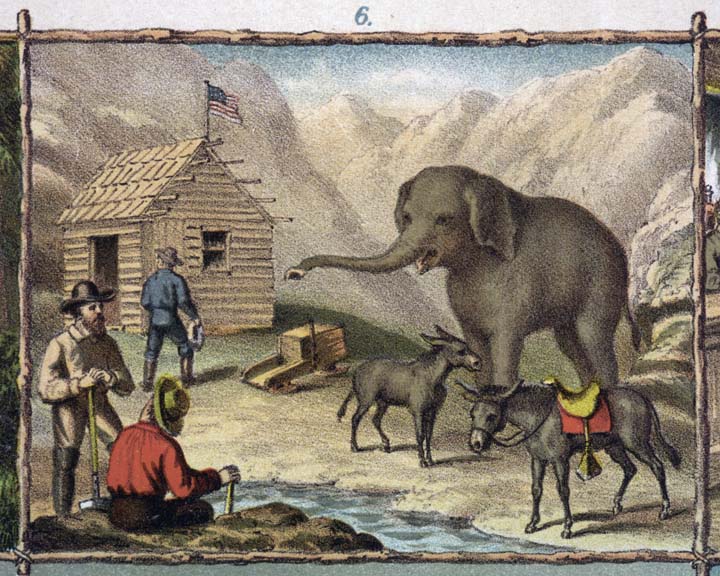

With the 1853 publication of James M. Hutchings’ The Miner’s 10 Commandments, the elephant ascends like a mastodonic Moses. Hutchings travels to California, along with 300,000 other fortune seekers, in the hope of striking it rich.

When Plan A doesn’t pan out, Hutchings turns his hand to writing and publishing. Here, he hits pay dirt. When first issued, The Miner’s 10 Commandments sells nearly 100,000 copies. Printed on letter sheet—a page of stationary that can be folded and sealed with the letter inside to form its own envelope—the Commandments center on a wandering miner to whom an elephant guide, not unlike a proboscidean Virgil, reveals an otherworldly moral code. Hutchings describes:

“I am a miner…and behold I’ve seen the elephant, yea, verily, I saw him, and bear witness, that from the key of his trunk to the end of his tail, his whole body hath passed before me; and I followed him until his huge feet stood before a clapboard shanty; then with his trunk extended he pointed to a candle-card tacked upon a shingle, as though he would say Read, and I read…”

Each commandment in the digger’s decalogue begins with a thou-shalt-not prohibition, suggesting the temptations rough-and-tumble miners face in a lawless land. The Commandments advise against jumping another prospector’s claim; taking one’s gold dust to the gaming tables; stealing shovels; and remembering what friends back home do on the Sabbath, lest the remembrance “…not compare favorably with what thou doest here.” However, Hutchings reserves his greatest cautionary zeal for Commandment VI: Thou Shalt Not Kill, which reads like a T.G.I.F. drink menu. The future Yosemite hotelier writes: “Neither shalt thou destroy thyself by getting ‘tight,’ nor ‘stewed,’ nor ‘high,’ nor ‘corned,’ nor ‘half-seas over,’ nor ‘three sheets in the wind,’ by drinking ‘brandy slings,’ ‘gin cocktails, ‘whiskey punches,’ ‘rum toddies,’ nor ‘egg-nogs’.” In the end, rather than pursue ephemeral riches at long odds, one was better served by Mark Twain’s sage advice: “During the gold rush, it is a good time to be in the pick and shovel business.”